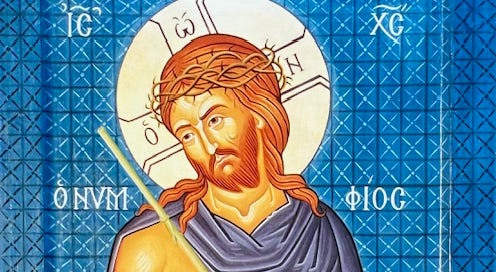

"Behold the Bridegroom comes in the middle of the night": the mysticism of gender and Holy Week

Because there are assumptions underlying this post concerning “gender” [1] and by extension, “sex,” it might appear that I’m being provocative, but it’s not my intention to provoke. My non-intentions aside, I will be assuming a few things in what follows. To begin with, I am assuming (and must assume) that it’s impossible for someone whose convictions are rooted in orthodox or classical Christianity to say – and actually mean it – that gender is a “social construct.” I will come back to this point briefly below. Likewise, ideally speaking, I assume that “gender” isn’t defined by a given society’s superficial “gender norms” (what is considered “appropriate” in attire, deportment, etc. in a culture). If there’s one thing gender certainly isn’t, it’s superficial. Lastly, what shouldn’t but often does need saying these days, is that gender isn’t simply another word for “sex” – masculine and feminine are not the same as male and female. This is something I’ll briefly come back to, as well. Such conceptual mistakes within the context of Christianity regarding what gender is – i.e., what gender manifests and means – are not mere trifles; they aren’t negligible or open to manipulation or alteration. Get the matter of gender wrong and one can’t get Christian thought or mysticism or piety or contemplation or “esotericism” (in the best sense) or “spirituality” or worship right. The justification for my insistence on this claim is that the Christian mystery (which, it must be stressed, is the single source of practical Christian “mysticism”), at its very heart, is profoundly nuptial, and therefore gender is at the core of its imagery.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Pragmatic Mystic to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.