From time to time — not often, but enough for me to note it as a sort of trend among those who feign theological sophistication — I will get a sort of sniggering reaction when I refer to C. S. Lewis (which I do, unabashedly) as a profound theological thinker. He was also something of a mystic, if by “mystic” we mean someone who intuited, or “glimpsed,” the spiritual reality just behind the visible surface of this world. Those who disdain him as a theologian do so for reasons too shallow, dull, and pretentious to enumerate. Many do so because they associate him with a form of Bible-only Evangelicalism they disapprove of; and while many in that populous camp do indeed revere Lewis, they’re neither representative of all those who have found in him a source of spiritual and imaginative nourishment (a body of people that includes a wide diversity of beliefs — Catholics, Orthodox, Jews, Muslims, and even atheists), nor are they representative of the essentially Anglican Christianity with which he quietly identified. Dismissing his theological mind goes along with other vapid complaints about him — he was a misogynist (he wasn’t), he was “simplistic” (perhaps the most obvious sign that someone has never really read him at any length), he was bigoted (he wasn’t), he could be a grouch (well, sometimes, no doubt), he’s no longer relevant (although a year rarely goes by without some new production about him appearing — this year, it’s a new motion picture), he wasn’t “modern” (he wasn’t, of course, which is what makes him a perennial), and so on. Long after his cultured despisers have vanished, and many already have, Lewis will continue to be read and celebrated. To those who don’t like him: live with it.

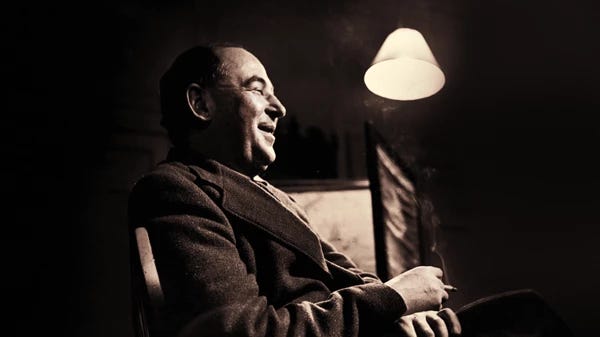

Today (November 29th) is his birthday. He was born in Belfast in 1898. A few days ago, some of us remembered the day of his death (November 22nd, 1963) which, of course, he — almost legendarily — shared with John F. Kennedy and Aldous Huxley. So, it seemed somehow right to offer you something about him today. Because this is a page with the word “mystic” in the title (and Lewis could be called a mystic, as I define the word, on the grounds of such books as — for instance — The Great Divorce, Surprised By Joy, and The Last Battle), I would like to share a few excerpts from a 2004 paper, entitled “Into the Region of Awe: Mysticism in C.S. Lewis,” delivered at Taylor University in Indiana by David C. Downing. (The entire address can be read by clicking here.) Following that, I would like to recommend a very fine BBC documentary, presented by A. N. Wilson, followed by two trailers — one of a recent film that can be found on various streaming services and another, as already noted, that will be released next month.

First, the excerpts from Downing’s essay:

Lewis is widely regarded as a “commonsense Christian,” one who offers theology that is understandable and morality that is practical. He stands in the mainstream of Christian tradition, avoiding sectarian disputes and writing for the ordinary reader.

Readers of Lewis who admire his middle-of-the-road metaphysics and his practical advice on daily living may be surprised by a sentence in Miracles where he describes "the burning and undimensioned depth of the Divine Life" as "unconditioned and unimaginable, transcending discursive thought" (160-161). They may be equally baffled by a passage in his memoir, Surprised by Joy, in which he describes his own conversion in overtly mystical terms: "Into the region of awe, in deepest solitude there is a road right out of the self, a commerce with . . . the naked Other, imageless (though our imagination salutes it with a hundred images), unknown, undefined, desired" (221).

Equally unusual passages may be found in Lewis’s fiction. In That Hideous Strength, for example, he describes a young seeker’s moment of conversion not in terms of her accepting a set of beliefs or joining a church. Rather it is a moment of dramatic personal encounter:

A boundary had been crossed. She had come into a world, or into a Person, or into the presence of a Person. Something expectant, patient, inexorable, met her with no veil or protection between. . . . In this height and depth and breadth the little idea of herself which she had hitherto called me dropped down and vanished, unfluttering, into bottomless distance, like a bird in a space without air. (318-19)

In these passages, and many others like them, we see that the common image of Lewis as a proponent of “rational religion” does not do justice to the complexity of the man. Lewis’s spiritual imagination was every bit as powerful as his intellect. For him, Christian faith was not merely a set of religious beliefs, nor institutional customs, nor moral traditions. It was rooted rather in a vivid, immediate sense of the Divine presence—in world history and myth, in the natural world, and in every human heart.

C.S. Lewis did not consider himself a mystic. In Letters to Malcolm, Lewis said that in younger days when he took walking tours, he loved hills, even mountain walks, but he didn’t have a head for climbing. In spiritual ascents, he also considered himself one of the “people of the foothills,” someone who didn’t dare attempt the “precipices of mysticism.” He added that he never felt called to “the higher level—the crags up which mystics vanish out of sight” (63).

Despite this disclaimer, Lewis must certainly have been one of the most mystical-minded of those who never formally embarked on the Mystical Way. We see this in the ravishing moments of Sweet Desire he experienced ever since childhood; in his vivid sense of the natural order as an image of the spiritual order; in his lifelong fascination with mystical texts; and in the mystical themes and images he so often appropriated for his own books. As his good friend Owen Barfield once remarked, Lewis, like George MacDonald and G. K. Chesterton before him, radiated a sense that the spiritual world is home, that we are always coming back to a place we have never yet reached (Stand 316).

According to Rudolf Otto in The Idea of the Holy, one of the defining traits of the numinous is a habitual sense of yearning, a deep longing for something inaccessible or unknown. Throughout his lifetime, Lewis had this kind of mystical yearning in abundance, the kind of long he called Joy or Sweet Desire. In The Problem of Pain Lewis confesses that “all [my] life an unattainable ecstasy has hovered just beyond the grasp of [my] consciousness” (136)…

Readers of Lewis know the details of his life well, including his life-long quest for the source of Joy, so I will focus here on how his reading of mystical texts, and his own mystical intuitions, contributed to his spiritual quest. Note for example a passage in Surprised by Joy in which Lewis discusses the loss of his childhood faith while at Wynyard School in England. He explains that his schoolboy faith did not provide him with assurance or comfort, but created rather self-condemnation. He fell into an internalized legalism, such that his private prayers never seemed good enough. He felt his lips were saying the right things, but his mind and heart were not in the words.

Lewis adds “if only someone had read me old Walter Hilton’s warning that we must never in prayer strive to extort ‘by maistry’ [mastery] what God does not give” (62). This is one of those casual references in Lewis which reveals a whole other side to him which may surprise those who think of him mainly as a Christian rationalist.

“Old Walter Hilton” is the fourteenth-century author of a manual for contemplatives called The Scale of Perfection. This book is sometimes called The Ladder of Perfection, as it presents the image of a ladder upon which one’s soul may ascend to a place of perfect unity and rest in the Spirit of God…

But when Lewis, at age seventeen, discovered MacDonald's Phantastes, it was an emotional and spiritual watershed. Reading the story for the first time in the spring of 1916, Lewis wrote enthusiastically to a friend that he'd had a "great literary experience" that week (Stand 206), and the book became one of his lifelong favorites. Over a decade later, Lewis wrote that nothing gave him a sense of "spiritual healing, of being washed" as much as reading George MacDonald (Stand 389).

Though he didn’t recognize it at the time, the young Lewis was responding warmly to the Christian mysticism that pervades all of MacDonald’s writing. Lewis later called MacDonald a “mystic and natural symbolist . . . who was seduced into writing novels” (Allegory 232)…

In his memoir Surprised by Joy Lewis described two conversion experiences, the first to a generalized Theism, the second to Christianity specifically, an affirmation that Jesus of Nazareth was God come down from heaven. The first of these occurred in the summer of 1929, centering on a mystically-charged experience that occurred while he was riding on a bus. Having affirmed that there is an Absolute, Lewis was increasingly attracted to Christians he had met at Oxford, especially J.R.R. Tolkien, and to Christian authors he had been reading, especially Samuel Johnson, George MacDonald, and G. K. Chesterton. Then one summer’s day, riding on the top deck of an omnibus, he became aware, without words or clear mental pictures, that he was “holding something at bay, or shutting something out” (224). He felt he was being presented with a free choice, that of opening a door or bolting it shut. He said he felt no weight of compulsion or duty, no threats or rewards, only a vivid sense that “to open the door . . . meant the incalculable” (224).

After the experience on the bus, Lewis took a full two years trying to figure out what it meant. He began by kneeling and praying soon afterwards, “the most dejected and reluctant convert in all England” (Joy 228). Then he started to explore a variety of spiritual and mystical texts. Though there are only scattered references to “devotional” reading in Lewis’s letters or diaries in his twenties, the two-year period 1929-31 finds him reading George MacDonald’s Diary of an Old Soul and Lilith, John Bunyan’s Grace Abounding, Dante’s Paradiso, Jacob Boehme’s The Signature of All Things, Brother Lawrence’s The Practice of the Presence of God, Thomas Traherne’s Centuries of Meditations, William Law’s an Appeal to All Who Doubt, Thomas a Kempis’ Imitation of Christ, as well as the Gospel of John in the original Greek.

All this thinking and reading came to a head in September 1931, when Lewis was persuaded by J.R.R. Tolkien and another Christian friend that Christ’s Incarnation is the historical embodiment of the Dying God myth, the universal story of One who gives himself for the sake of his people. Lewis’s second conversion, his acknowledgment that Christ is God, once again came while riding, this time in the sidecar of his brother Warren’s motorcycle.

Of all the texts Lewis read during his spiritual apprenticeship, one that affected him the most was the Gospel of John (in Greek), which he said made all other religious writing seem like a comedown He also responded strongly to Jacob Boehme’s The Signature of All Things (1623). Upon his first reading in 1930, Lewis said it had been “about the biggest shaking up I’ve got from a book since I first read Phantastes” (Stand 328). After talking about qualities of horror and dread which made Boehme less pleasant than MacDonald, Lewis concludes, “It’s not like a book at all, but like a thunderclap. Heaven defend us—what things there are knocking about in the world!” (Stand 328). Part of what filled Lewis with uneasy fascination was Boehme’s portrayal of God when there was nothing but God. The Book of Genesis begins with God in the act of creation. But Boehme goes back a step and describes, “the eternal Stillness,” a noplace and notime with only the Infinite Being and Non-Being. Perhaps more importantly, Lewis encountered in Boehme the first fully-articulated system of nature-mysticism…

For Lewis nature mysticism was not so much a philosophy as a deeply realized sense of joy and gratitude in the beauty of the natural world. He liked all kinds of weather and loved to fill his letters with minute descriptions of landscapes, farmyards, forests, skies, stormclouds, and sunsets. He often made explicit the spiritual resonances he saw in the natural world. In one letter he compares the woods at Whipsnade Zoo, with their bluebells and birdsong, to “the world before the Fall” (Letters 154). In another he says that early morning luminosity of a country churchyard before Easter service “makes the Resurrection almost seem natural” (Unpub ltr, Mar 29, 1940)…

Jack’s own health was not good in the years following Joy’s death. He suffered from heart and kidney disease and began receiving blood transfusions in 1961. He had a heart attack in July1963 and went into a coma. After receiving Last Rites, he surprised everyone by waking up from his coma and asking for a cup of tea. Though he was comfortable and cheerful, Lewis never fully recovered from this condition. He died quietly on November 22, 1963.

Considering Lewis’s adolescent interest in conjuring apparitions, it seems ironic that he himself should experience such a vision, unbidden, in the last months of his life. Walter Hooper reports that, one afternoon during Lewis’s hospitalization in July, he suddenly pulled himself up and stared intently across the room. He seemed to gaze upon something or someone "very great and beautiful" near at hand, for there was rapturous expression on his face unlike anything Hooper had seen before. Jack kept on looking, and repeated to himself several times, "Oh, I never imagined, I never imagined." The joyous expression remained on his features as he fell back onto his pillows and went to sleep. Later on, he remembered nothing of this episode, but he said that even speculating about it with Hooper gave him a "refreshment of the spirit" (Essays 27-28).

There is little doubt that such an experience was related to Lewis’s serious medical condition. Nonetheless, it seems fitting that for once, fleetingly, the “unattainable ecstasy” he’d been seeking his whole life was something to be grasped, an assurance of things unseen.

Rudolf Otto wrote that Christianity is not a mystical religion, because it is not built upon private intuitions. Rather he calls it a historical faith with “mystical coloring.” Perhaps Otto’s description of Christian tradition may fit individual Christians as well. Though Lewis did not claim to be a mystic, his faith always displayed a distinct mystical coloring, an iridescence of rich and glittering hues.

*****

“CS Lewis's biographer A.N. Wilson goes in search of the man behind Narnia - best-selling children's author and famous Christian writer, but an under-appreciated Oxford academic and an aspiring poet who never achieved the same success in writing verse as he did prose.”

*****

The Most Reluctant Convert (2021) is, I must say, perhaps the best dramatic film on Lewis that has yet been made. I enjoyed both film versions of Shadowlands (especially the first, made for television and featuring the late Joss Ackland in the role of Lewis), but this new production is superb in quality and absorbing in content. Based on the stage play written by Max McLean, who also — impeccably, in my opinion — portrays Lewis, it is not to be bypassed. As already mentioned above, it is found on streaming services (I recently saw it on Apple+) and it’s well worth “the price of admission.” Here is the trailer:

*****

Lastly, here is the trailer for Freud’s Last Session, based on another play (this one fictional), to be released in December. In it, Freud and Lewis engage with one another on such matters as mortality and faith — something that never occurred in life, but might have. The picture looks promising. Anthony Hopkins, who portrayed Lewis in the theatrical version of Shadowlands, portrays Freud this time around. Obviously, we will just have to wait and see if it’s as good as the trailer suggests, but I’m certainly looking forward to its release.

Thank you for this. I have noticed the rather dismissive tone toward Lewis, which seems to be quite prevalent right now. Perhaps it is partly an overcorrection in response to the sometimes intemperate veneration by some Evangelicals, who also tend to have a rather sanitized version of Lewis' thought. But it has a bit of the tone of hipster superiority about it.

Lewis was wrong on some things, and had some odd gaps in his theological thought. So it is with all of us. I have come to find his version of the free will defense of hell, for example, quite inadequate. On the other hand, how many people have been helped toward a more capacious understanding of the grace of God, rescued from appalling fundamentalist visions of retributive punishment?

Of course, I can't prove it, but I suspect the current renaissance of universalism would not have happened without Lewis' influence.

I am currently on my third read through of the Narnia books with my 7 year old daughter, who adores them. And even as an adult I find myself often moved to tears by these simple books. Lewis had profound gifts as a mythopoetic storyteller, and for many of us, our initiation into the Christian imagination came through his books. His vast influence has been almost entirely to the good.

His discussion of Matthew's "be ye perfect" in Mere Christianity jingles around in my head - I signed up for a bit of spiritual growth and here I am revisiting the entirety of my life, all of my shortcomings and the people I have hurt, and trying to find ways to life faithfully in areas I never even imagined... it started small and here I feel like the rug is being pulled out!

Similar thoughts for the Christian evaluation of pride as the root of our sin. I can't say definitively as he did that no other religion sees pride as Christianity does, but I can say that seeing my shortcomings through the lens of my own pride has been most helpful in growing in love of God, neighbor, and self.

Whatever worries one may carry about associations with American evangelicals, Lewis was a master of his craft and such a pleasure to read.