My previous post was about the great interpreter of Confucianism, Mencius (372 – 289 B.C.), and was focused particularly on those themes in his book that can appropriately be regarded as “mystical.” While there has never been a cinematic treatment of the life of Mencius (alas), two have been made based on the life of his master (once removed), Confucius (c. 551 – c. 479 B.C.), and both are worth seeing. Some of you may be familiar with the 2010 film, with Chow Yun-fat (of Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, etc. fame) in the central role. Generally garnering tepid reviews, I appreciate it and think it offers much to praise. The earlier film, made by the renowned Chinese director, Fei Mu, in 1940, was believed to have been lost forever until it was found and restored in 2009. It is rightly regarded as a classic of Chinese cinema. Happily, both films are available for viewing on YouTube for free (at least, they are at the moment), and both have English subtitles.

Certainly, as I noted in my Mencius article, Confucianism is considered a “humanist” philosophy and not generally regarded as mystical. This can be misleading, however, since both religious ritual and contemplative practice were considered important (indeed, central) by Confucius. In classical Chinese philosophy, the Confucian and (philosophical) Taoist perspectives are held together — the warm, dry yang of ethical Confucianism is tempered and complemented by the cool, moist yin of mystical Taoism (which was continued, with Buddhist overlay, in Ch’an). What some see as a tension between these two traditions is, in fact, a dynamic interaction. There can be no true mysticism without ethics or righteous pursuit, just as there can be no depth of root for ethics without the fertile soil of a healthy mystical grounding.

Here are the links to the two films, with some introductory comments.

*****

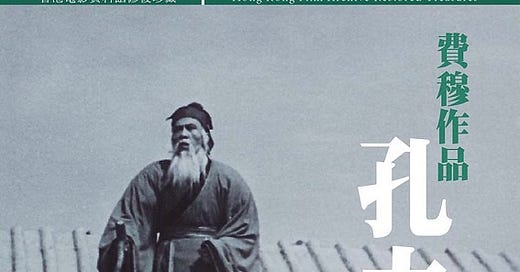

Fei Mu's Confucius (1940)

The film is described on the DVD edition that was released in 2009 in this way:

Unlike the common perception today of Confucius as a hallowed hero, the title character in director Fei Mu's Confucius (1940) is portrayed as a ‘stray dog' – from his failure to influence the politics of his own state, to his futile quest to propagate humanity across the land. Confucius is a meditation on integrity and morality through a man of extraordinary virtue – in a time of Chinese history when there were no morals at all.

Fei Mu masterfully combines the arts of theatre and film in creating a pared-down aesthetic rarely found in Chinese historical dramas. This seminal piece in Chinese cinema, considered lost for over 50 years, finally sees the light again after being found and restored by the Hong Kong Film Archive.

David Bordwell writes the following in an article about this classic film (the full article can be read by clicking here):

… All this makes the discovery of a print of Confucius (1940) an event of capital importance. An anonymous individual donated a print to the Hong Kong Film Archive, which spent years restoring it in collaboration with L’Immagine Ritrovata of Bologna. In the donated print of Confucius, some portions of the soundtrack had liquefied, so some stretches are silent, and there are about nine minutes of fragments that have yet to be integrated.

At the premiere, a very useful booklet on the film’s restoration was given out, and moving introductory speeches were presented by Barbara Fei Ming-yee, the director’s daughter, and Serena Jin, daughter of the producer Jin Xinmin. The screening added electronic subtitles that not only translated the dialogue but identified each speaker—a helpful gesture for a film with many characters and a tangled intrigue.

I can’t comment on it as a representation of Confucius’ thought and life, although experts tell us that it is quite different from the elevated, almost sanctified portrayals that were known before. The plot dramatizes the ineffectuality of the sage’s ideals of civic virtue by showing how power players of his era ignored or undercut his teachings. Scenes from Confucius’ life alternate with scenes of political and military strategy, as warlords and statesmen debate tactics and, not incidentally, calculate how to eliminate Confucius. As Confucius migrates across China, he is unable to halt the continuous warfare among various factions. His disciples leave or die. Just before his death he has only his grandson to care for him. “A great educator, thinker, and philosopher,” Fei Mu writes in an essay, “Confucius was doomed a victim of the politics of his time.”

The film is slow-moving and hieratic. Some of the fragments show bits of violence, but the film as a whole relies on dialogue. Although some scenes unfold in natural exteriors, Fei Mu often employs theatrical tableaus, complete with painted landscapes; occasionally the actors cast shadows on the backdrops. The cutting is often axial, simply enlarging a chunk of space as actors declaim their dialogue. The nearly square Movietone frame enhances the symmetry of the compositions, which often feature a window or some other aperture.

Knowing the fluid style of Fei’s 1930s films, we can only regard this rigid, rather ceremonial look as a deliberate artistic choice. In this respect, the film recalls Eisenstein’s Alexander Nevsky and Mizoguchi’s Genroku Chushingura, films of that era aiming to treat a weighty historical subject with solemnity. In Confucius, Fei seems to have been rethinking the relation of cinema to theatre, a quest that preoccupied other directors of the period and that remains important today. Wong Ain-ling’s essay in the booklet aptly notes Rohmer’s Perceval le Gallois as a more recent parallel, and the film likewise has some of the feel of the Straub/ Huillet version of Von heute auf morgen (1997). As often happens, Fei Mu feels like a modern filmmaker.

There are a few patchy moments in the film, without sound, but it rewards the time and effort one gives to it.

*****

Confucius (2010)

About this film, Variety had this to say (full review here):

Though he was probably the last person on most people’s lists to play the venerable Chinese philosopher, Chow Yun-fat makes a commanding screen presence as “Confucius.” Combining calm sagacity with a potent physicality that more than fills helmer Hu Mei’s big visual stage, Chow carries the biopic almost single-handedly and prevents it from becoming overly respectful…

Tightly constructed pic, which shows signs of having been edited down from a longer cut, has a pacey tempo without seeming rushed, and is immeasurably helped by Zhao’s score, which smoothly binds together the shifts from scholarly discussions to scenes of war. Lean but lavish production and costume design, using the huge stages of Hengdian World Studios in Zhejiang province, color-code the various kingdoms for visual appeal without becoming as operatic as Zhang Yimou’s recent costumers (set during later, lusher eras).

I apologize, but having found a fellow admirer of Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, I can't help but say something, and I haven't any skill to talk about film. I, too, have wondered why so many did not appreciate the film. (It should go without saying that you have to watch the subtitled version.) Not only was the story interesting and the film exceptionally beautiful, but the characters were complex, and the film took the time to develop the otherwise not quite hidden inner tensions that was driving the plot. Chow Yun-fat played the master perfectly, not falling into cliche, surrendering both to his tradition/discipline while not denying his humanity and destiny. I thought it a perfect romance on many levels. I could probably go on but I will spare all the humiliation of my gushing.

That said, thanks for the link, I look foward to watching these.