There have been three television series – just three – which I can in all honesty say have influenced my personal “philosophy” as much as any book ever has. Although this admission will date me, each of these programs appeared respectively in the 1960s, the 1970s, and the 1980s. The first, which entered my life in 1967, when I was an impressionable eleven-year-old, was The Prisoner with Patrick McGoohan (its creator and star). It was a startlingly odd and thought-provoking fictional tale that, over the course of seventeen episodes, dealt primarily with individual freedom vis-à-vis the overreaching machinations of a manipulative ultramodern society. Whether the equivocally named “Village” was capitalist or socialist, right or left didn’t really matter; it masqueraded as democratic, but its true nature was creepily authoritarian and soul-crushing. The controversial twist at the end of the series steered it away from caustic social satire and into psychology and the problem of the individualist ego – but I won’t say any more about the series here. Perhaps I might return to it in a future post.

The third of the three programs mentioned above was Bill Moyers’s illuminating interviews with the mythologist Joseph Campbell, The Power of Myth, which aired in 1988, one year after Campbell’s death. Few programs have offered such a wealth of insight in a mere six hours.

But it’s the second series of the three with which I’m concerned here. The Long Search was a thirteen-episode journey that explored the experience of living religion around the globe. Beautifully filmed and intelligently presented (no “History” or “Discovery Channel” treatment this; this was the BBC and PBS during their intellectual heyday), the program first aired in 1977. It was the brainchild of Ninian Smart (1927 – 2001), the renowned scholar of comparative religion. But it was Ronald Eyre (1929 – 1992), at the time a British television writer and theater director (and an agnostic), who made the long trek, interviewing representative figures of each religion he investigated, closely observing everything along the way, and making trenchant commentary throughout. You can still find a handful of the episodes on YouTube and Internet Archive, but alas, not the entire series. As recently as the early 2000s, I was still using the series in classes for students at Northern Illinois University. Eyre followed up the TV program with a book in 1979, and – now that the former is difficult to find – I’m very glad that I have a copy of the latter.

And all the above is my roundabout way of getting to an introduction of the third and fourth terms I want to define (maybe “sketch” is a better word) for this Substack page. Last time, I looked cursorily at mysticism and pragmatism. Regarding mysticism, I said that it “means primarily a disciplined reliance on intuition and introspection for the sake of apprehending what underlies, permeates, and transcends everything our common senses and reason are able to grasp.” As for pragmatism, following William James, we saw that it refers to an empirical method – in other words, it is experimental, active, and concerned with “what works.” Theory, speculation, doctrine, dogma, metaphysics, systems of thought – without denigrating any of these things (in their place), a pragmatic mysticism is concerned with the practitioner’s actual engagement, encounter, and personal experience. It’s only concerned with roots that bear fruits.

The next two terms I wish to discuss – because together with the first two they indicate how I understand my own inner life – are perennialism and individuation. And both words, no doubt obscure to some readers, are open to misunderstanding by just about everybody. Here, however, is precisely where The Long Search comes to the rescue. Ronald Eyre’s final episode of the series and the final chapter of the book provides a summary of what he gleaned from his travels, and his concluding reflections – along with insights he received from the philosopher Jacob Needleman (1934 – 2022) – will aid me in fleshing out what both terms mean to me.

There have been various schools of “perennialism”[1] (the name comes from philosophia perennis, a term coined in the 16th century), a philosophy that – to put the matter simply – sees the world’s religions as sharing in a single metaphysical reality. Without a doubt, the best-known perennialist of the 20th century was Aldous Huxley (1894 – 1963). His 1945 book, The Perennial Philosophy, described perennialism in this way on its very first page: it is, he wrote, “The metaphysic that recognises a divine Reality substantial to the world of things and lives and minds; the psychology that finds in the soul something similar to, or even identical with, divine Reality; the ethic that places man's final end in the knowledge of the immanent and transcendent Ground of all being — the thing is immemorial and universal.” (The idea that perennialism isn’t merely a philosophical or speculative metaphysic, but also an engaged “psychology,” points us back to what we said about pragmatism and ahead to what we will say about individuation.)

The year before his book on perennialism appeared, Huxley had written an introduction to the translation of the Bhagavad-Gita, translated by Swami Prabhavananda and Christopher Isherwood, in which he succinctly listed what he called the four “fundamental doctrines” of the perennial philosophy:

First: the phenomenal world of matter and of individualized consciousness–the world of things and animals and men and even gods–is the manifestation of a Divine Ground within which all partial realities have their being, and apart from which they would be non-existent.

Second: human beings are capable not merely of knowing about the Divine Ground by inference; they can also realize its existence by a direct intuition, superior to discursive reasoning. This immediate knowledge unites the knower with that which is known.

Third: man possesses a double nature, a phenomenal ego and an eternal Self, which is the inner man, the spirit, the spark of divinity within the soul. It is possible for a man, if he so desires, to identify himself with the spirit and therefore with the Divine Ground, which is of the same or like nature with the spirit.

Fourth: man’s life on earth has only one end and purpose: to identify himself with his eternal Self and so to come to unitive knowledge of the Divine Ground.[2]

(Aldous Huxley)

There’s a lot to unpack in Huxley’s definition and four doctrines, and I would recommend at this stage going back over them slowly and thoughtfully. One possible objection to be gotten out of the way right at the start, however, is the observation that “not all religions say the same thing.” Indeed, they don’t, and Huxley doesn’t say they do; he is saying, however, that at the core of all the great religious and mystical traditions there exists a single reality – the very reality that embryonic mysticism intuits, and pragmatic mysticism actively seeks to know better.

And so, I return to Ronald Eyre, Jacob Needleman, and their interchange in the concluding chapter of The Long Search.

Eyre addresses this same canard that all religions say the same thing: “When, as often happened [during Eyre’s travels], someone suggested that all the Great Religions say the same thing, I have never known how to respond.”[3] He continues with a mountaineering analogy: “Perhaps all the Great Religions say the same thing in the sense that all mountaineers climb mountains. But that does not mean that all the ascents are the same, though it is perfectly true that all ascents are about going up.” He goes on with this analogy, likening the different practices and traditions to different climbing kits – each kit suited to the sort of climb one is attempting. He then offers a warning to those who presume that their particular “kit” – their own tradition – is the best choice for every other “climber”/ “seeker/believer” that comes along: “[T]he very idea of leaning across and shouting abuse to another climber – whether you have in mind a religion or mountains – seems to me contemptible and dangerous and silly. Somewhere on the rock-face too there may be a hint of an answer to the question: ‘Which religion is best?’ Which would be parallel to the question: ‘Which mountaineering kit is best?’ A mountaineer would presumably answer: ‘Show me your mountain and I’ll show you your kit.’”

(Ronald Eyre, as he appeared in The Long Search.)

In other words, Eyre notes both the common endeavor of the spiritual or religious quest universally, while sensibly noting that “one size doesn’t fit all.” Each tradition grows out of a specific cultural milieu, has its own history of development, and uses different language, imagery, and symbols to evoke what lies beyond all words and concepts. (And even within a single tradition, there can be varieties of practice. For example, in Catholicism, there is a Benedictine “way,” a Franciscan “way,” a Jesuit “way,” and so on. Within Buddhism, we see a wide diversity of schools. And this variety is found within virtually every great tradition.) The “kits” differ from climber to climber. The climb is what can be called perennial, or perhaps – to extend the analogy – it is the summoning heights, the pinnacle, the open vast heaven above that has a perennial draw.

Even more to the point where the pragmatic or our active involvement is concerned, what is perennial in all these quests is the call to be transformed. Both inwardly and outwardly, what is absolutely non-negotiable and at the heart of spiritual life in every one of the great traditions is change. This was the crux of Eyre’s discussion with Jacob Needleman, which I quote at some length below. Writes Eyre:

I had asked him a question about change. If, as seems the case, we are under constant pressure from Teachers and Teachings to change, to be born again, to realize our Buddha-nature, to be made alive in Christ, to crack the small self and understand our identity with the large Self, what is the first step to take, the basic beginner’s move? At first we sparred. ‘In order to have any kind of exchange on the subject,’ he said, ‘I’d want to know from you what you hit against in life, what makes you want to change. Just change for the sake of change? No. You want to be happy? It’s not that really. There are many things being offered to make you happy in some sense. In response to your question, I think the first step I feel being urged on me by the Great Teachings is to look into myself and see what it is about myself that I wish to understand; to look, to observe, to study myself as an unknown entity, something that I have never seen before. Now this is the step that is missing very often in religions both old and new. They start a little too high. They start with us as though we already know what we want, as though we’re ready to make our commitments. But we are not. We are much below that. A real practical mysticism that could really work change would, I feel, have to start with the work of studying myself as I am.[4] That is the rung of the ladder that is left out.’ Still on the level of creeds and commitments, I persisted: ‘What should I do? Should I sit? What’s the action?’ To which he answered: ‘Could you do it now, now while we are talking?’ ‘Why not?’ I countered, still talking but the words dribbling away: ‘I mean, if there is some technique…’ He broke in sharply: ‘I am not asking you off camera. I am asking you on camera. Now. As I am talking to you. Could you do it? Could you see what you are – now?’ ‘You mean to say,’ I shifted, ‘it’s not just a technical matter?’ ‘It’s not a technical matter. It’s not a question of sitting in a lotus posture or being in church or having a guru. There is something right now preventing us from knowing who we are.’

… We began again with what seemed like the same question: ‘Let’s say that somebody says to you, “Fine. I understand that change and growth has to be gradual, in one cell, one person at a time. But what do I have to do to set about making myself available for change?” What would you say to that person?’ He hesitated. ‘I am not going to answer you the way I did before because that was before and I don’t feel the same thing in your question.’ (Pause.) ‘To be available for change, you have to make room, I think. This is what you get if you read or approach the Great Teachings in a state of need rather than a state of curiosity. In a state of need you are not just interested in getting information; you are willing to set something aside, to give something up… “What are you willing to give up for it?” …

‘That question, when it comes back to you, is a measure of your sincerity. It’s a measure of your seriousness. And perhaps you see that you are not all that serious: “I just wanted to know what you were thinking, Buddha. I didn’t want you actually to do anything to me.” And the Buddha will say, perhaps, “Well, all right. That’s fine. Goodbye.” So the question that comes back to us is: “How serious are you? What do you really want?” … Can we answer that? I think we cannot. I think we are left speechless with that… What I think we come back to if we ask your question [which was, you remember, What do I have to do to change?] is “Who are you?” “Who’s asking?” The moment that that question is asked, you get into a real relationship with the Teaching, because you see your lack. You have a need (even if it is not the need you thought you had, which was for the Great Truth), you have a need to be in contact with yourself at this moment, and you see that you haven’t been in contact with yourself. At this point you are in a real relationship because you are empty, not in contact, wish to be in contact, wish to be more situated in yourself, wish to have what they call the Presence, Being. You wish to be. In that state you can hear the language, hear the symbols, feel the presence of the Teacher in a very different way from when you started. And I think, you know, it’s along these lines that real exchange takes place; not with giving creeds, giving doctrines, giving pamphlets. There is not enough time in life to read pamphlets. You have to have the relationship with the Teacher… and the Teaching.’

(Jacob Needleman)

There’s much in this conversation between Eyre and Needleman to take in, and careful reading and re-reading of it are rewarding. The central “perennial” message in Needleman’s words, though, might be reduced to “seek and you shall find”; but the seeking must be in earnest, must begin with one’s self (which isn’t merely one’s ego), must be open to change, and must primarily be about encountering “the Divine Ground” (to use Huxley’s inadequate phrase) — and not just wanting information, a body of ideas, theoretical concepts, a neat definitive creed, or a head trip. Each “great teaching” is just one entrance into a vast temple. Each of us enters it through an individual — usually a culturally determined — door. Once inside, though, one may be surprised or even scandalized to discover that many have entered through other doors – in fact, the “wrong” doors, some might be inclined to surmise. But in this temple, there can’t be any wrong doors for the most basic of reasons: we must go through them from each of our own contexts. One enters from Europe, another from Asia, another from Africa, and so on. And what’s to be explored once we are inside the temple may not be what we imagined or planned when we crossed the threshold of our respective door. Inside is a reality that challenges expectations. Reality exceeds all our favored presuppositions. But the true entrance in every case is found – as Jacob Needleman pointed out to Ronald Eyre – within our own “hearts” (an old, old metaphor that refers to the integrated self).

Here we can turn our attention from perennialism to a cursory look at individuation, a term that comes from the school of psychology originating with Carl Jung (1875 – 1961). As noted in passing above, individuation is not to be confused with individualism. Individualism, as Jung described it, “means deliberately stressing and giving prominence to some supposed peculiarity, rather than to collective considerations and obligations.”[5] In other words, it’s a way of standing out from the crowd, of presenting an outwardly different and indivisible character to the world. It is ego-centric, a projection of the ego.

The ego, however, is only a part of our whole psyche – it is only one aspect of the “self” and a relatively small aspect at that. While the psyche is “the totality of all psychic processes, conscious as well as unconscious,”[6] the ego is, in the words of Ann Hopwood, “the centre of the field of consciousness which contains our conscious awareness of existing and a continuing sense of personal identity. It is the organiser of our thoughts and intuitions, feelings, and sensations, and has access to memories which are not repressed. The ego is the bearer of personality and stands at the junction between the inner and outer worlds.”[7] In other words, our ego is good and necessary, but it doesn’t exhaust “who we are” (bringing us right back to Jacob Needleman’s pointed questions directed at Ronald Eyre above).

“Individuation,” then, is an inward process, an inner integration of all the areas of our psyche, bringing to conscious awareness all those other aspects of ourselves – including those things we consciously and unconsciously repress within ourselves. “[F]or Jung consciousness rests on the unconscious, not the other way around,” writes Bernardo Kastrup. “This implies… that the unconscious and consciousness have the same essential nature, in the same way that a flower has the same vegetable nature of the plant that produces it… [T]he background activity of the unconscious influences and organizes the foreground activity of consciousness.” Kastrup continues:

Perhaps even more importantly, Jung posits that the foundations of the unconscious [within our psyches] are collective and transpersonal, as opposed to being confined to any individual psyche. As such, the unconscious can be divided into two segments: the personal unconscious – which, like consciousness, is bound to a particular individual – and the collective unconscious. The latter is the foundational segment, older in an evolutionary sense and shared by all human beings…

The structure and contents of the collective unconscious are a priori: they predate the rise of both consciousness and the personal unconscious…

The picture we are left with is that of a psyche divided into three layers: the bottom, primordial layer is the collective unconscious… The middle layer, sandwiched between the other two, is the personal unconscious. The top layer, which we normally identify with, is ego-consciousness.[8]

(Carl Jung)

Think of your psyche, then, as a vast ocean, its deepest deeps inaccessible to you and its shallower depths only apprehended by the ego in dreams and imaginings and – sometimes – by your own inexplicable moods and behaviors. In comparison, your ego – your conscious waking self – is like a small island or vessel that’s always at the mercy of your (inner) elements. What Jung is proposing, what Needleman was proposing to Eyre, and – in fact – what all the “great teachings” of the world and throughout the ages propose, is that the beginnings of wisdom are planted within us from our creation, in one’s depths. Here it is that one enters the temple or climbs the mountain and encounters what cannot be conveyed in words. As Needleman put it above, “A real practical mysticism that could really work change [in us] would, I feel, have to start with the work of studying [ourselves as we are].”

Evelyn Underhill, whom I cited in my earlier post, eloquently described all this and the essence of individuation in her book Mysticism more than a hundred and ten years ago. Without knowing the term, which was to come later, she already understood it as crucial for developing a deep interior life. “We know… that the personality of man is a far deeper and more mysterious thing than the sum of his conscious feeling, thought, and will: that this superficial self – this Ego of which each of us is aware – hardly counts in comparison with the depths of being which it hides… The mystic way must therefore be a life, a discipline, which will alter the constituents of his mental life as to include this spark within the conscious field: bring it out of the hiddenness, from those deep levels where it sustains and guides his normal existence, and make it the dominant element round which his personality is arranged.”[9] Or, as Jung might have said, we must do the inner work necessary to make the unconscious conscious.

Here I must apologize for such a lengthy post. I’ve thrown an awful lot out on the table and, over time in these Substack posts, it will be further sifted and explored. But this is a good place to pause and catch our breaths. In the next post, I will pick up where this post left off and, in relation to what has gone before, talk about God.

[1] One school which I intentionally avoid is that associated with the Swiss metaphysician, Frithjof Schuon. Without going into any discussion here as to why that is, I direct the curious to this research paper: https://www.academia.edu/8979853/A_Dance_of_Masks_The_Esoteric_Ethics_of_Frithjof_Schuon?email_work_card=title.

[2] The entire introduction can be read online here: https://processbahai.wordpress.com/introduction-to-the-bhagavad-gita-by-aldous-huxley/.

[3] Ronald Eyre, Ronald Eyre on the Long Search (Cleveland/New York, 1979). In what follows, I draw from pages 275 to 280 of the text.

[4] Emphasis mine. This sentence cuts to the core of what I mean by “pragmatic mysticism.”

[5] Jung, Collected Works (CW) 7, paragraph 267.

[6] Jung, CW6, para. 797.

[7] See: https://www.thesap.org.uk/articles-on-jungian-psychology-2/carl-gustav-jung/jungs-model-psyche/#:~:text=Jung%20saw%20the%20ego%20as,memories%20which%20are%20not%20repressed.

[8] Bernardo Kastrup, Decoding Jung’s Metaphysics: The Archetypal semantics of an Experiential Universe (Winchester, UK, 2019), p. 33.

[9] Underhill, Mysticism, pp. 51, 55. Emphasis mine.

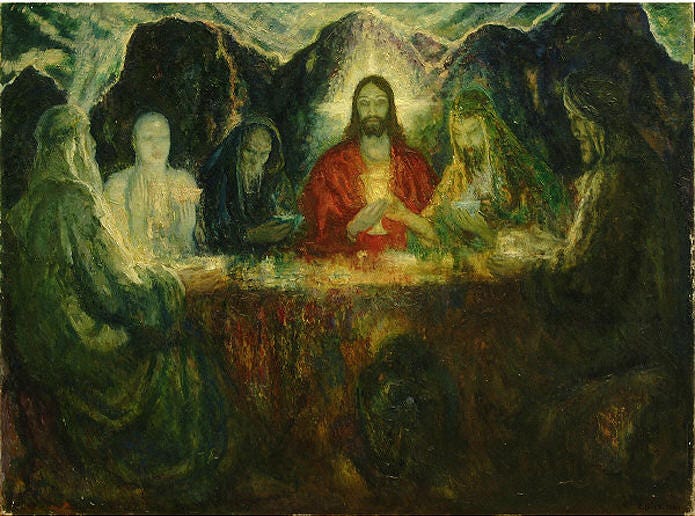

(Francis Luis Mora, 1874 – 1940, “The Eternal Supper,” 1926. In the painting are depicted Moses, Buddha, Lao-Tzu, Christ, Confucius, and Zoroaster.)

"In this temple," there are *different* doors, but "no wrong doors." - This piece is too good to be read quickly, as I just did. I'll be back. You walk this talk so well in your "The Ox-Herder and the Good Shepherd: Finding Christ on the Buddha's Path" (2013). - I just discovered that "The Long Search" series (BBC) was re-issued on DVD, and is currently distributed by "Ambrose Video" but is planned for Netflix. See https://www.netflixtvseries.com/tv/47685/the-long-search. - Thanks for your own work on this.

Needleman’s Lost Christianity is a great book (really), and is his deepest Christian engagement I know of. He single handedly rescued a living modern heir of the Christian desert mystic tradition from certain obscurity. And it seems that Underhill’s Practical Mysticism, not just Mysticism, is ripe for the plucking in future posts. Published after the war started, I find it much more helpful than Mysticism. Perhaps it hints at where this exciting substack is headed.