Julian of Norwich: a recommended BBC video documentary (free post)

Mystic, theologian, anchoress, and the first female writer in the English language whose work survives

On May 8th, the Church of England (to which I belong) and Anglican churches around the world commemorate Dame Julian of Norwich (c. 1342 - c. 1423). Her book, Revelations of Divine Love, is remarkable for many reasons. That the manuscript survives at all is just short of miraculous, as the documentary posted below makes strikingly evident. It is also the first extant text in English by a woman. And, most importantly for many of us, her visions are theologically rich and wonderfully provocative. During one of the two periods that stand out in the history of English spirituality (the 14th century), which saw such inspiring works produced as those of Richard Rolle, Walter Hilton, and the anonymous author of The Cloud of Unknowing, Julian’s text now stands as possibly the most well-beloved of them all — and for good reason (incidentally, the second great age of English spirituality was during the 17th century). As Karen Murdarasi wrote this past February in Premier Christianity:

Julian saw a number of visions or ‘shewings’ while near to death and during her recovery. Although she initially wrote them off as delirium, she was later convicted that they were truly messages from God. She also decided they were not just for her, but for all people. She wrote her visions down so that the message could be shared with everyone who was interested. In doing so she became the first identifiably female writer in the English language, or at least the first whose work has survived. Julian may have been married and even had children, we don’t know. Although people often assume that she must have been a nun when she had her visions, she actually seems to have been living at home during her illness, with her mother and parish priest at her bedside.

What we do know is that later in life she became an anchoress: a female anchorite. This was someone who, instead of joining a convent, lived a type of monastic life in a ‘cell’ (a room or suite) usually attached to a church. Once anchorites entered their individual cells they would stay there until they died, but they could have visitors, usually people looking for spiritual advice. Julian, as an elderly anchoress, gained a reputation for wisdom, and was visited by the younger mystic Margery Kemp, among others. But it is her visions as a young woman that she is now remembered for.

Murdarasi refers to Julian as “a secret radical,” and provides the evidence:

Some of the things Julian said or implied are hardly orthodox Church doctrine, and might even be described as subversive. Julian started with the assumption of a God whose wrath burned against sin and sinners, but that was not what she saw in her visions. The God she met could not be angry.

He was entirely loving, with no room for anger or blame, even against sin. Sin, in fact, does not really exist in the conventional sense, because ‘God is all things’ and ‘God does all things’, and there is no sin in him. The suffering caused by sin does exist, but it was part of God’s plan because it made people humble and repentant, so that they returned to God. Julian even suggested that the suffering we cause ourselves through sin draws us closer to Jesus because it is like sharing his sufferings on the cross. ‘Sin is not shameful to man, but his glory’ because God’s grace will turn it to glory.

Of course, a world in which sin doesn’t really exist and God never blames anyone for anything doesn’t tie in well with the idea of hell. Julian struggled with how it can be true that ‘all shall be well’ if there are souls suffering in hell for eternity, as the Church taught. God’s answer to her, in her vision, was that he would do something at the end of time so that ‘all shall be well’. Exactly what he would do was not revealed, but this final action would make ‘all well that is not well’. Despite Julian’s frequent protestations that she believed all Church teachings, she comes awfully close to universalism: the idea that everyone will be saved. Julian accepted that those who love sin are separated from God, but she added ‘if there are any that do’.

Julian lived at least into her 70s and was regarded with respect by local people, so despite her unorthodox beliefs she avoided being labelled a heretic. Her revelations remain a source of comfort and inspiration to many, perhaps because they show that even a nameless woman, ‘ignorant, weak and frail’ is immeasurably precious in the eyes of an immeasurably loving God.

(You can read the entire article by Karen Murdarasi here.)

Below is a superb hour-long documentary, produced by the BBC, detailing the loss and recovery of Julian’s historic text. Here is a description of the program, taken from the website of Dr. Janina Ramirez:

The Search for the Lost Manuscript: Julian of Norwich.

In this hour-long documentary, Dr Janina Ramirez tells the incredible story of a book hidden for centuries in the shadows of history, the first book ever written in English by a woman, Julian of Norwich, in 1373.

Revelations of Divine Love dared to present an alternative vision of man's relationship with God, a theology fundamentally at odds with the church of Julian's time, and for 500 years the book was suppressed. It re-emerged in the 20th century as an iconic text for the women's movement and was acknowledged as a literary masterpiece.

Janina follows the trail of the lost manuscript, travelling from Norwich to Cambrai in northern France to discover how the book survived and the brave women who championed it.

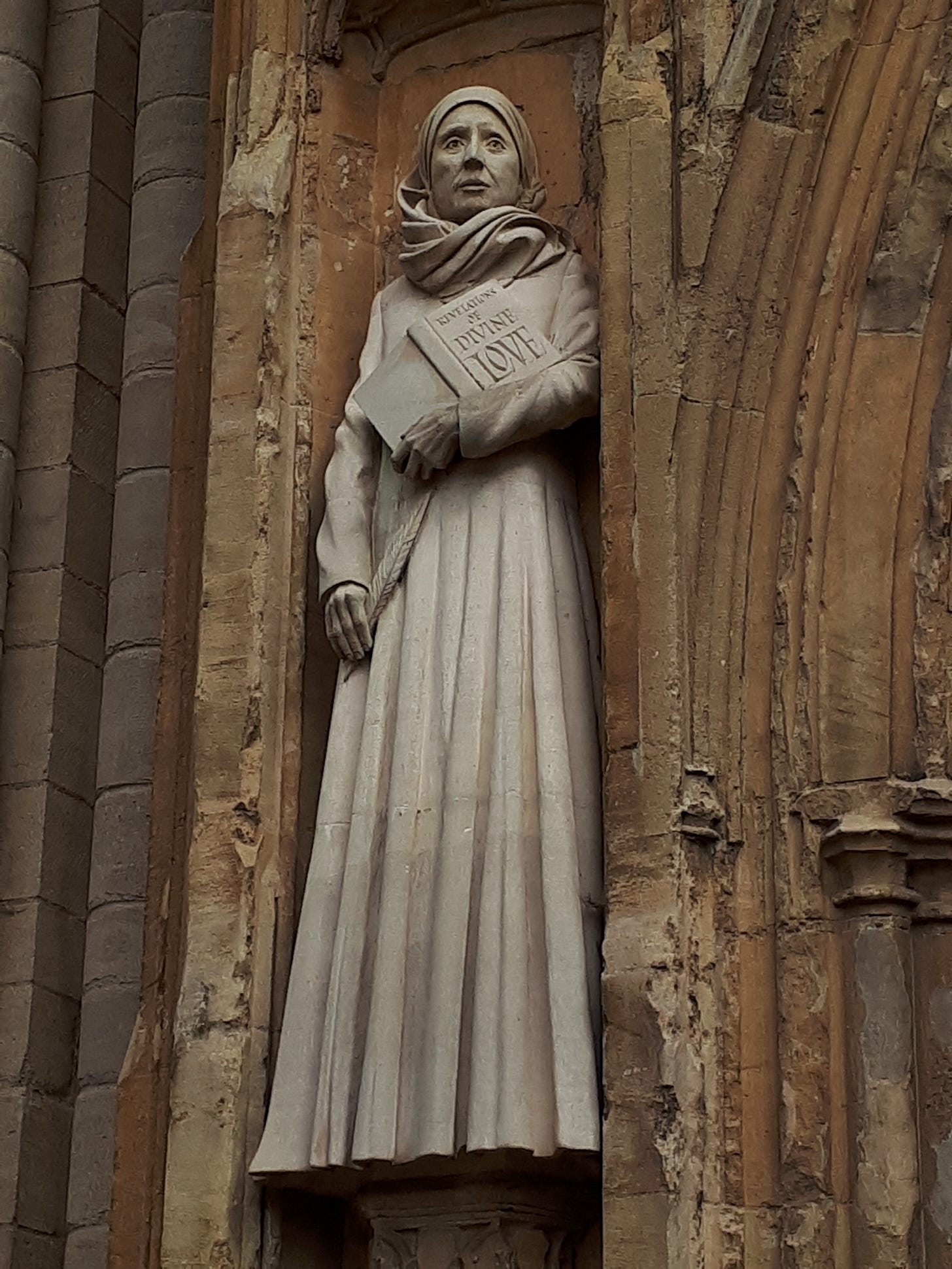

(A photograph I took outside Norwich Cathedral in 2019.)

“ Julian accepted that those who love sin are separated from God, but she added ‘if there are any that do.’”

And, of course, how could they? Sin qua sin cannot be loved; God is Love, and “in Him there is no darkness at all.” How can one not love Love?