Mysticism and music 3: Ralph Vaughan Williams and the "Five Mystical Songs" of George Herbert (free post)

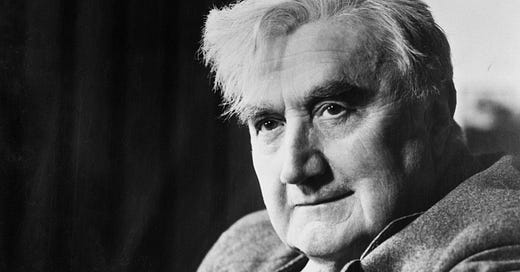

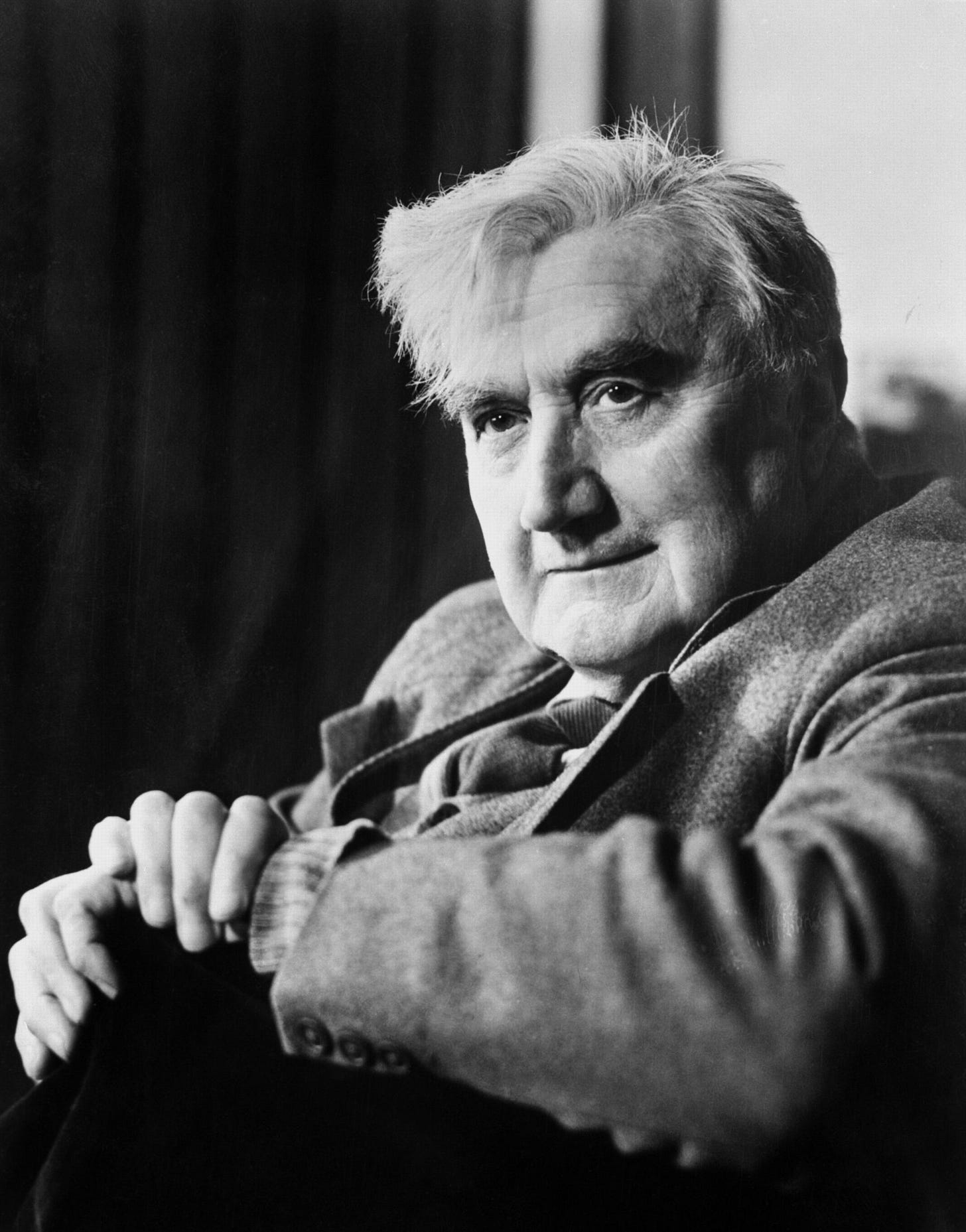

The atheist and the Anglican poet-priest

The first post in this series, “Mysticism and Music,” featured Gustav Holst’s “The Hymn of Jesus.” Holst was, of course, a great friend of this post’s featured composer, Ralph Vaughan Williams (1872 - 1958). (Vaughan Williams, I readily confess, is one of my favorite composers of any age.) Unlike Holst, it can’t be said of him that he was a “mystic.” At the same time, it can’t be denied that virtually all his works — from his evocative orchestral pieces to his nine tremendous symphonies, to his vocal and choral masterpieces (for both church and stage), to his chamber music — convey a developed sense of the sublime, a profound longing, an elusive sensibility, and (I don’t hesitate to say) the mystical. His work on the English Hymnal (1906), with the scholarly priest and liturgist Percy Dearmer (1867 - 1936), was a landmark production in the rich tradition of Anglican church music. This, it should be noted, despite the fact that Vaughan Williams was an atheist at the time; he was later described as “a cheerful agnostic.” But throughout his life, he was never far removed from religion or religious music, and he evidently felt no antagonism or bitterness toward faith; much the reverse. He poured his heart into giving musical expression to it, and one can’t help believing it reveals his own inner yearning for the transcendent. By the time he composed his 1951 opera, The Pilgrim’s Progress, his interest in world religions had, in fact, become marked.

There are two superb video biographies of Vaughan Williams to be found on YouTube, both moving and providing ample examples of his works. You can view them here:

Most of you will know this particular orchestral piece (if only for its inclusion in the 2003 film, Master and Commander):

But in this post, I wish especially to highlight his “Five Mystical Songs,” composed between 1906 and 1911. John Bawden has written this fine, succinct description of these pieces (which can be found here):

Following the death of Purcell in 1695, English music went into a long period of decline that was not reversed until the late 19th century with the emergence of Elgar, followed by a whole new generation of talented composers. The leading figure of this younger group of musicians was Ralph Vaughan Williams, who for nearly sixty years remained one of the most influential figures in English music, his nine symphonies and succession of major choral works being widely regarded as his greatest achievements.

Like Elgar, Vaughan Williams was a late developer, reaching his mid-thirties before attracting serious attention as a composer. He eventually developed his own unique musical style, which was profoundly influenced by his love of Tudor music and his immensely important work in collecting English folksongs. In 1908 Vaughan Williams studied with Ravel for a brief three months, and shortly afterwards produced a series of major works, including the song-cycle On Wenlock Edge, the Fantasia on a theme by Thomas Tallis and, in 1911, the Sea Symphony and the Five Mystical Songs, the latter a setting of poems by George Herbert (1593 – 1633). Despite his declared atheism, which in later years mellowed into what his wife Ursula described as ‘a cheerful agnosticism’, Vaughan Williams was inspired throughout his life by much of the liturgy and music of the Anglican church, the language of the King James Bible, and the visionary qualities of religious verse such as Herbert’s. The baritone soloist is prominent in the first four of the Mystical Songs, with the chorus taking a subsidiary role. In the opening song, the lute and its music are used as a metaphor for the poet’s emotions at Easter. The second song features a simple but moving melody for the baritone soloist, who is joined by the chorus for the third verse. In the third song the choir can be heard intoning the ancient plainsong antiphon, O sacrum convivium, whilst the fourth movement, The Call, is for baritone solo. An accompaniment suggestive of pealing bells introduces the triumphant final song of praise, in which the chorus is heard to full effect.

The poems of Herbert, presented in the video below with Vaughan Williams’ compelling musical settings, are the following:

Easter – from Herbert's Easter

Rise heart; thy Lord is risen.

Sing his praise without delayes,

Who takes thee by the hand,

that thou likewise with him may'st rise;

That, as his death calcined thee to dust,

His life may make thee gold, and much more, just.

Awake, my lute, and struggle for thy part with all thy art.

The crosse taught all wood to resound his name, who bore the same.

His stretched sinews taught all strings, what key

Is the best to celebrate this most high day.

Consort both heart and lute, and twist a song pleasant and long;

Or since all musick is but three parts vied and multiplied.

O let thy blessed Spirit bear a part,

And make up our defects with his sweet art.

***

I Got Me Flowers – from the second half of Easter

I got me flowers to strew thy way;

I got me boughs off many a tree:

But thou wast up by break of day,

And brought'st thy sweets along with thee.

The Sunne arising in the East.

Though he give light, and th'East perfume;

If they should offer to contest

With thy arising, they presume.

Can there be any day but this,

Though many sunnes to shine endeavour?

We count three hundred, but we misse:

There is but one, and that one ever.

***

Love Bade Me Welcome – from Love (III)

Love bade me welcome: yet my soul drew back.

Guiltie of dust and sinne.

But quick-ey'd Love, observing me grow slack

From my first entrance in,

Drew nearer to me, sweetly questioning

If I lack'd anything.

A guest, I answer'd, worthy to be here:

Love said, You shall be he.

I the unkinde, ungrateful? Ah, my deare,

I cannot look on thee.

Love took my hand, and smiling did reply,

Who made the eyes but I?

Truth Lord, but I have marr'd them: let my shame

Go where it doth deserve.

And know you not, sayes Love, who bore the blame?

My deare, then I will serve.

You must sit down, sayes Love, and taste my meat:

So I did sit and eat.

***

The Call – from The Call

Come, my Way, my Truth, my Life:

Such a Way, as gives us breath:

Such a Truth, as ends all strife:

Such a Life, as killeth death.

Come, my Light, my Feast, my Strength:

Such a Light, as shows a feast:

Such a Feast, as mends in length:

Such a Strength, as makes his guest.

Come, my Joy, my Love, my Heart:

Such a Joy, as none can move:

Such a Love, as none can part:

Such a Heart, as joyes in love.

***

Antiphon – from Antiphon (I)

Let all the world in ev'ry corner sing:

My God and King.

The heavens are not too high,

His praise may thither flie;

The earth is not too low,

His praises there may grow.

Let all the world in ev'ry corner sing:

My God and King.

The Church with psalms must shout,

No doore can keep them out;

But above all, the heart

Must bear the longest part.

Let all the world in ev'ry corner sing:

My God and King.

***

Great article, which I read while in London. This before I saw a wonderful concert featuring Messiaen's L'Ascension and Mahler's Symphony # 4. Talk about elements of mysticism, the ending of L'Ascension left the audience stunned, or so it seemed to me. I love Vaughan Williams and of course the English music of the 16th century.

Thank you! Much appreciated!