In his 1980 book, Lost Christianity, which I read when it was first published and today regard as something of a modern classic, Jacob Needleman (see my Substack post for August 5th) has much to say about locating and abiding in the “intermediate” — in what the tradition calls the heart — as being essential to authentic (what he means by “lost”) Christianity. It has to do with practice, both in corporate worship and private devotion: learning to focus one’s attention — in fact, achieving “purity of attention” (“Blessed are the pure in spirit…”) —, which is neither a rational exercise nor an indulgence in one’s emotions. It’s something in between the two; which is where the concept of “the soul” becomes important. In classical Christianity, one’s “soul” is not separate from the body, not a “ghost in the machine”; rather, it is the life, the center, and the binding force of the whole psychosomatic being. Citing such Christian thinkers as Gregory of Nyssa, Symeon the New Theologian, a certain and rather mysterious “Father Sylvan,” and others, Needleman shows this practice of learning gradually to abide interiorly in the “intermediate” to be something other than “subjective experiences of thought, emotion, or sensation.” The “intermediate” “is not mind or reason as we ordinarily experience them; not familiar emotions, no matter how intense or how exalted their object; not ‘personal identity’ in the sense of the social self.” “Without the appearance of the ‘intermediate,’ the teachings of Christianity — the morality, the call to faith and to love, the work of sacrifice or service — simply cannot enter into a man” (p. 152). “Father Sylvan” is quoted as writing, “The language of our teaching is for the heart and the mind simultaneously. It is not for the emotions” (p. 209). At one point, he notes that our emotions conceal the heart. In other words, we must get past both them and our rationalism to find the heart.

I bring all that up because, despite the title of Needleman’s book, I don’t believe that the tradition has been so much “lost” as obscured and untaught. Anyone familiar with the Christian spiritual tradition (and the sources are readily available) — The Philokalia in the East, for example, or the writings of, say, the Cistercian, Carthusian, and Carmelite spiritual masters in the West — knows that the tradition, in essence, isn’t lost. The problem has been the officialdom, the pull of politics, and the “worldly” social distractions within the churches themselves; all too frequently and scandalously those “keepers of the tradition” who should have been teachers (see Hebrews 5:12) have left unearthed an incalculable hoard of spiritual riches which they should instead have opened up and learned how to distribute. It’s little wonder that “destitute” Christians have often sought for spiritual enrichment elsewhere. As fond as I am of Zen, for example, there’s nothing in that tradition that can’t be found in the Christian spiritual tradition (and I’m biased enough to say I could never trade the latter for the former). Wherever disciples have access to the great, ancient tradition, Christianity hasn’t been “lost” at all; everywhere else, however…

But this isn’t the purpose of this post.

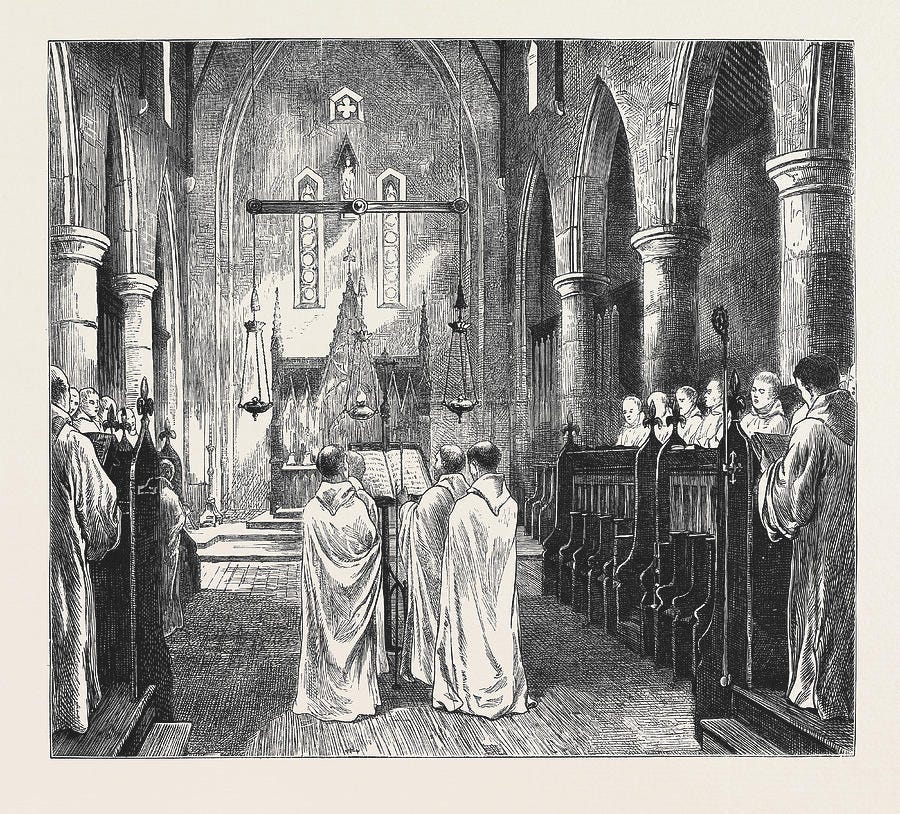

Rather, I want to exemplify this tradition of finding and abiding in the “intermediate” — the heart, the soul — in Christianity by drawing attention to its tradition of liturgical expression. Of course, that tradition is vast and rich and includes countless musical styles, from ancient times to the present day. But the tradition in its purest form is found in the chant. Most religions of the world practice chanting in some form, including those — like Buddhism — that are non-theistic. Chants are verbal (based on important texts), repetitious, often unaccompanied by musical instruments, and have an intentional meditative or (in some cases) ecstatic quality. And, given what we read above, they are vehicles for reaching that “place” beyond the coolly intellectual and the hotly emotional. In short, religious chant is the music of contemplation. At its most effective, it steers the mind to meditate on the words chanted, inflected as they are by the melody, rhythm, or sometimes by just a barren and steady monotone.

Christian chant dates from ancient times, influenced by modal Hebrew chant. It was in Syria where Hebrew and Hellenistic forms of music became integrated and formed the backbone of Christian chant. Both the Byzantine and Latin traditions of chant emerged from this combination of influences. Gregorian chant, with its eight “church modes,” is a direct descendant of this musical legacy. As the music that became intimately linked to Western monasticism, Gregorian chant can be regarded as quite nearly a musical form of lectio divina (see my two posts on that subject). Reading and chanting become one thing by means of it: it becomes meditation inspired by the vocal and aural.

Below you will find what I consider to be among the best recordings available online, exemplifying a variety of related types of Christian chant.

Between the 11th and 13th centuries, Gregorian chant gradually superseded the more ancient “Old Roman” chant in the Latin West. Here is a selection of the “Old Roman” — what you might have heard sung had you, say, paid a visit to St. Peter’s in the 900s. As you listen, take note of how these Latin texts are sung in a style that suggests to the ear music we would (quite rightly) associate with the Middle East. The Syrian connection is clearly evident.

Ambrosian chant, named for St. Ambrose, comes from Milan.

Mozarabic chant or Visigothic chant (also called Old Spanish chant) can be dated to the 7th century or earlier.

Gregorian chant, named for St. Gregory the Great, is the most familiar in the Western tradition. I regard it as the epitome of contemplative music. This magnificent German collection also includes selections from Ambrosian chant.

For those who may feel the need for a periodic “shot in the arm,” the diurnal round of chanted liturgical Offices is available each day online — either at their website or by subscribing to their podcast — from the Abbey of Barroux in France. You can visit them by clicking here.

Lastly, for the sake of a bit of balance, I would be in the wrong not to provide an example of Byzantine chant. After John of Damascus, the greatest name in Byzantine chant is that of Ioannis Papadopoulos Koukouzelis, “the Angel-Voiced,” an Albanian of the 13th and 14th centuries. He was highly regarded by the emperor in Constantinople, but despite his prestige at court, he became a monk on Mount Athos. He is regarded as a saint, and his feast day in the Orthodox Church is on October 1st (mark your calendar now).

If you look to the slavic lands the fascniating mutation of Byzantine chant into Znammeny chant is remarkable which of course mutated further into the modern 8 Obikhod tones of the Russian Church and the startling beauty that inspired so many composers in their own musical expression.

Thanks for providing us with more spiritual riches in these exemplary recordings of Christian chant. So far I like the “Old Roman” the best, but they are all very beautiful and restorative.