Reading ancient spiritual texts intelligently

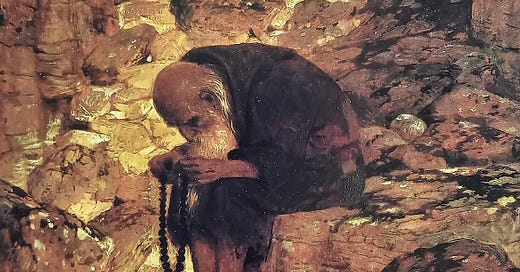

A case study: Theophanis the Monk’s “The Ladder of Divine Graces”

Whether we are encountering the sacred canonical scriptures of a given faith tradition (the Hebrew Bible, the New Testament, the Vedas, the Quran, and so on) or the innumerable spiritual and mystical texts that orbit the same throughout the succeeding ages, or – as in the case of some traditions – orbit no foundational canonical writings at all, what is required of the modern reader is a respectful but critical mindset. My assumption, of course, is that what contemporary readers of spiritual texts desire is simultaneously to understand them in their original context and how to apply them to their lives today. For readers who don’t have these aims in view, such writings may seem impenetrable or even foolish. For them, the texts remain closed, yielding nothing, or they are badly misinterpreted. And then there are modern readers who read ancient texts much too literally, as if they were reading the works of contemporaries. They come to these writings initially with openness, but because they fail to discern the differences between their own cultural and historical context and that of the past (sometimes long past), they can go away feeling overburdened or unnecessarily troubled by what they read. They find, perhaps, that they can’t live up to the expectations or adopt some of the views of their ascetical heroes (imagine trying to take upon oneself Abba Arsenius’s ideal that only “one hour of sleep each night should be sufficient for a monk,” for instance, or regarding that same figure’s misogyny as anything less than a blight on his character). My concern is that we who are serious about engaging the old texts of our traditions should know how to read them without dismissing them on the one hand or accepting everything in them uncritically on the other. There’s a sensible “middle way” to approach them that steers clear of the inanities of both progressivism (in which the insights of the past are judged by the most up-to-date assumptions of the present – what C. S. Lewis called “chronological snobbery” –, which in turn works like a prophylactic against receiving ancient wisdom as wisdom) and literalism (which is to “reading comprehension” what a shipwreck is to a voyage). We must, in other words, read old texts intelligently – meaning both respectfully and critically – if we want to read them to our benefit. The old analogy applies: we eat the fish and spit out the bones. We savor the meat, and we don’t regret tossing out the bones we can’t swallow. (“Therefore every scribe who has been trained for the kingdom of heaven is like a householder who brings out of his treasure what is new and what is old”; Matt. 13:52.) The best way to explain what I mean is to illustrate it with a specific text. To that end, I’ve chosen a short poetic writing with the cumbersome title, “The Ladder of Divine Graces which experience has made known to those inspired by God,” taken from the third volume of The Philokalia, that vastly important treasure trove of Eastern Christian mystical texts, which appears under the name of Theophanis the Monk.[1]

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Pragmatic Mystic to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.