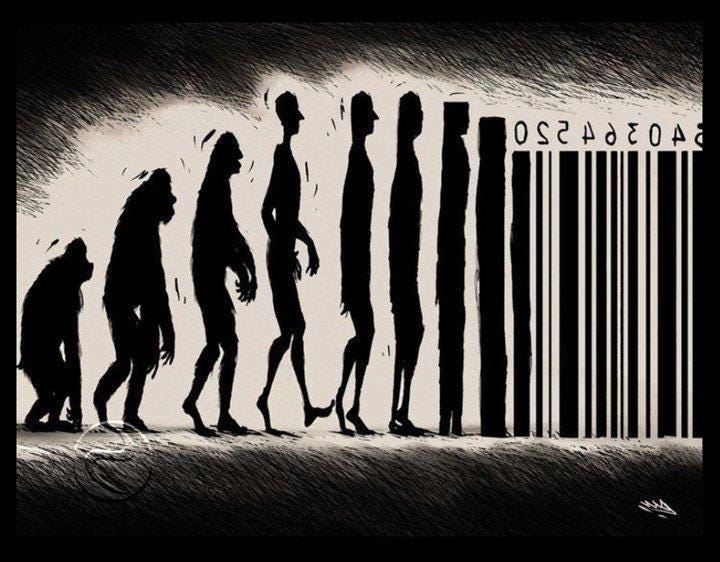

Recently I made the assertion on Facebook that the slogan “Love is Love” is — when taken objectively as the statement of an idea — banal. Of course, there were those who agreed with me (some for reasons different than my own) and others who didn’t. My reason for calling it banal (I compared it to “It’s the Pepsi Generation”) had to do with its appeal to something other than the intellect. “Love,” for example, isn’t defined in the phrase, the presumption being that we should already know what’s being referred to; but “love” is one word that begs for definition whenever it’s used. Unfortunately, English has this one four-letter word to express everything from “I love my paramour” (finally, a rare opportunity to use “paramour” in a sentence) to “I love my mother” to “I love baseball” to “I love the smell of napalm in the morning.” Those who disagreed with my remark objected for two reasons that I recall. The first was on the grounds that I didn’t appreciate the “context” of the slogan (although, frankly, since I’ve seen it posted — in English — even here in this small town in Norway, it has found its way into my context and therefore couldn’t evade my scrutiny). The second reason was that any criticism of the slogan (or any slogan, I suppose) must be “pedantic.” Well, maybe it is; I prefer, though, to think that my comment was based on the fact that I had merely thought about it. And it’s not the only politically charged slogan I’ve thought about in recent years that’s vacuous — aimed, as it is, at the emotions, bypassing the intellect, and intended to stir up an unpremeditated response. For example: “Make America Great Again.” What we have in both instances is, in essence, advertising. Someone is trying to sell us something before we have had the chance to examine the product. It aims at the subliminal while simultaneously appealing directly to our appetites, preferences, prejudices, wants, or emotions. This sort of thing is a mark of our society, of course, and has been for a long, long time. But it’s a problem. For those with any spiritual or contemplative acuity, it’s especially so.

I want to be clear here. Not all slogans (the word has military origins, referring to the cry or chant of armed warriors) are thoughtless or banal. One must be discerning. Some slogans, like the chants used at sports events or meaningfully in protests, do make sense in their immediate context. But I’m referring to those specifically employed for shutting down thought and healthy debate — commercially, politically, ideologically, and as propaganda — and not just in an “immediate” context. These are the “memes” (by which I mean more than what one sees on social media) that are thrown out into the public arena and intended to manipulate our minds (I could say our “souls” or psyches). They can be used to sell us stuff, they can be used to stir up resentment or anger in us, they can be used to shame, or to gather the troops (like those who stormed the Capitol on January 6, 2021) — but they’re always aimed at convincing us of something before the critical faculty can come into play (as it rightly should). Slogans — like battle cries — go for the emotions, the gut, those areas in us that are quick to react, whether it’s to engage in fight or retreat in flight or to capitulate (“Big brother is watching you”).

Meditation and contemplation, practiced regularly, will almost invariably make us less susceptible to being either triggered or manipulated by slogans and the like. Practices such as Zen meditation or the Hesychastic prayer tradition of Eastern Christianity — to name but two, but almost any serious meditative tradition will result in this — will make us more critical, not less so, when we are confronted with “ideas” that really aren’t ideas, “thoughts” that primarily engage not our minds but our feelings or passions, and anything smacking of propaganda or advertising. There are, to be honest, forms of “spirituality” that do not rise to the level of meditative practice to which I refer — a lot that passes for spirituality begins and ends with what “feels good” to the practitioner (pardon the coarse analogy, but there is such a thing as spiritual masturbation). But true contemplative practice isn’t about warm fuzzies (“feelz”), affirming one’s individual identity, wish fulfillment, or having some relaxing experience of inner peace and bliss. It’s about encountering reality — the reality of God, of our psyches, of life as it is, of the fact of death and what lies beyond. In that endeavor, there’s no place for advertising, propaganda, political and ideological allegiances, or manipulative thoughts (in classical terms, these are not all that distinct from the “demonic”). Every path we are urged to go down demands our scrutiny. And slogans are always on hand to urge us in all sorts of directions. This is not an argument for being non-engaged socially or politically, but rather to be engaged with sharpened wits and spiritual independence.

*****

With all this in mind, I leave you with two television series, both dealing in their ways with our society and the psyche — and what we should be constantly wary not to trust as regards the former. Neither series will help you meditate, but both should prove entertaining and enlightening. And, as a bonus, I’ve tacked on a short cartoon at the end (penned by R. Crumb — whose oeuvre I would normally not recommend to those trying to keep their minds clean, but in this case, it’s (pardon the term) a “natural”).

The first is Adam Curtis’s indispensable four-part documentary, The Century of the Self. About it, Wikipedia says:

In episode one, Curtis says, "This series is about how those in power have used Freud's theories to try and control the dangerous crowd in an age of mass democracy."…

The Century of the Self asks deeper questions about the roots and methods of consumerism and commodification and their implications. It also questions the modern way people see themselves, the attitudes to fashion, and superficiality.

The business and political worlds use psychological techniques to read, create and fulfill the desires of the public, and to make their products and speeches as pleasing as possible to consumers and voters. Curtis questions the intentions and origins of this relatively new approach to engaging the public.

Where once the political process was about engaging people's rational, conscious minds, as well as facilitating their needs as a group, Stuart Ewen, a historian of public relations, argues that politicians now appeal to primitive impulses that have little bearing on issues outside the narrow self-interests of a consumer society.

The words of Paul Mazur, a leading Wall Street banker working for Lehman Brothers in 1927, are cited: "We must shift America from a needs- to a desires-culture. People must be trained to desire, to want new things, even before the old have been entirely consumed. [...] Man's desires must overshadow his needs."

In part four the main subjects are Philip Gould, a political strategist, and Matthew Freud, a PR consultant and the great-grandson of Sigmund Freud. In the 1990s, they were instrumental to bringing the Democratic Party in the US and New Labour in the United Kingdom back into power through use of the focus group, originally invented by psychoanalysts employed by US corporations to allow consumers to express their feelings and needs, just as patients do in psychotherapy.

Curtis ends by saying that, "Although we feel we are free, in reality, we—like the politicians—have become the slaves of our own desires," and compares Britain and America to 'Democracity', an exhibit at the 1939 New York World's Fair created by Edward Bernays.

I feel certain that this series will alter how you perceive your culture. It may even drive you to deeper prayer. Here is the playlist:

*****

Once again, I recommend the brilliant 1967 series, The Prisoner. The brainchild of Patrick McGoohan, nothing like it had ever been seen before (and, I doubt that anything quite like it has been made since). It is an extended social commentary (and it’s a social commentary on every modern society, the predominant ideology of any given one notwithstanding), and it ends on a distinctly psychological note. It has something to say to every individual person and — I would argue — provides grist for the spiritual-intellectual mill. And it’s fun. I was twelve years old in 1968 when it premiered in the US, and I confess that it has exercised an influence on my view of modern society ever since, nor can I count how many times I have rewatched it. I never get tired of seeing it again. One must make allowances for the fact that it was made nearly sixty years ago. But it holds up. Only too well. Note, if you watch it, the role that slogans play throughout.

Wikipedia describes the series this way:

The Prisoner is a 1967 British television series created by Patrick McGoohan, with possible contributions from George Markstein. McGoohan played the lead role as Number Six, an unnamed British intelligence agent who is abducted and imprisoned in a mysterious coastal village. Episode plots have elements of science fiction, allegory, and psychological drama, as well as spy fiction…

A single series of 17 episodes was filmed between September 1966 and January 1968, with exterior location filming in Portmeirion, Wales. Interior scenes were filmed at MGM-British Studios in Borehamwood, north of London. The series was first broadcast in Canada beginning on 5 September 1967, in the UK on 29 September 1967, and in the US on 1 June 1968. Although the show was sold as a thriller in the mould of the previous series starring McGoohan, Danger Man, its combination of 1960s countercultural themes and surrealistic setting had a far-reaching influence on science fiction and fantasy TV programming and on narrative popular culture in general. Since its initial screening, the series has developed a cult following.

The series follows an unnamed British man (played by McGoohan) who, after abruptly and angrily resigning from his highly sensitive government job – apparently a secret service post – prepares to go on a trip. The most he will later reveal about his resignation is that it was a "matter of conscience" and that he was "not selling out". While packing his luggage, he is rendered unconscious by knockout gas piped into his London home.

When he wakes, he finds himself in a re-creation of the interior of his home, located in a mysterious coastal settlement known to its residents as "the Village". The Village is surrounded by mountains on three sides and the sea on the other…

Here is the link, which can only be viewed by clicking below, which will take you directly over to YouTube:

*****

And here is our promised cartoon added feature:

As always, grateful for your words. Excellent, enlightening, needed.

A very enjoyable, enlightening post, thank you. I've never cared much for R Crumb's work (I find his images rather ugly), but I liked this one very much indeed. It reminds me a little of the story of Markandeya, particularly as it is presented in Peter Brook's Mahabharata. If any of you have a spare ten minutes (and I'm sorry I couldn't find it in one single post), it's well worth a listen. There's something incredibly deep about the Indian religious mind sometimes.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZqZX2k0xW2k

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=osjtI-CEGgA

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PkdHWFMNokw