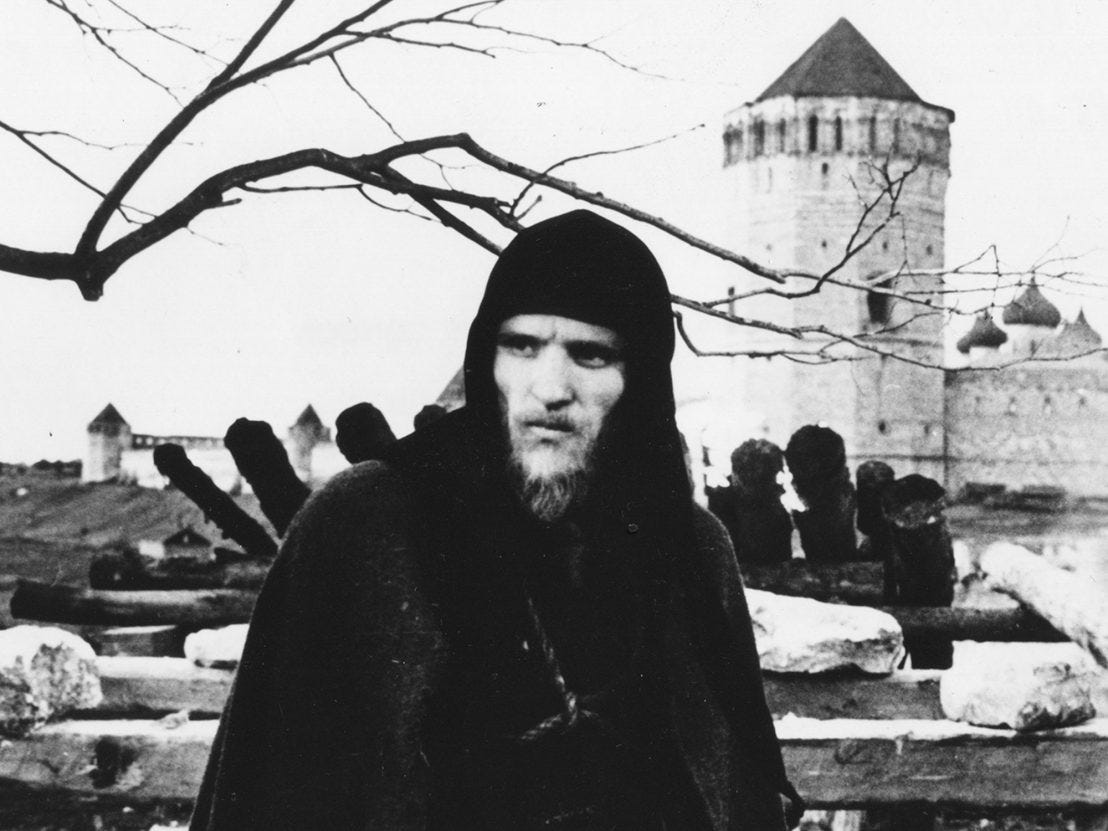

There are few films as strikingly existentialist and mystical simultaneously as Andrei Tarkovsky’s sprawling, magnificent three-hour-plus film, Andrei Rublev (1966). Loosely based on the life of Russia’s greatest iconographer, the 14th/15th-century St. Andrei Rublev (his feast day in the Orthodox Church falls on July 4), Tarkovsky (1932 - 1986) ingeniously used his medium to explore faith, sin, hope, the precariousness of life in a world rife with brutality and viciousness (a theme that is perennial and immediately relevant in light of current events in Palestine and Israel and in Ukraine), transcendence, and the hunger of the human soul to find the sacred through art. It is described on the Criterion website (you can read the entire article by clicking here) in these terms:

Andrei Rublev is itself more an icon than a movie about an icon painter. (Perhaps it should be seen as a “moving icon,” in the same sense that the Lumière brothers made “moving pictures.”) This is a portrait of an artist in which no one lifts a brush. The patterns are God’s, whether seen in a close-up of spilled paint swirling into pond water or the clods of dirt Rublev flings against a whitewashed wall. But no movie has ever attached greater significance to the artist’s role. It’s as though Rublev’s presence justifies creation.

Tarkovsky the cinematic artist has achieved the status of a director’s director. As a New Yorker essay on him and his films noted:

Among directors, Tarkovsky has become a godlike figure, his signature motifs imitated to the point of becoming clichés. He is the chief exemplar of what is sometimes called slow cinema, in which the camera lingers in long takes on austere landscapes and scenes of minimal activity. (The average shot length in Tarkovsky’s final three films is a minute or more; in a modern action movie, it’s usually a few seconds.) In the journal Sight & Sound, Nick James wrote, “If there are grasslands swirling, white mist veiling a house in a dark green valley, cleansing torrential rains, a burning barn or house, or tracking shots across objects submerged in water, a Tarkovsky name-drop is never far away.” Terrence Malick, Claire Denis, Shirin Neshat, Béla Tarr, Alejandro González Iñárritu, Christopher Nolan, and Lars von Trier, to name a few, display Tarkovskyan traits. Admirers have proliferated in other realms as well. Elena Ferrante reveres him, and Patti Smith has a song called “Tarkovsky,” which includes the line “Black moon shines on a lake, white as a hand in the dark.”

For those, however, who would portray him as a Russian nationalist, harboring messianic illusions about his homeland, the article adds this cautionary paragraph:

[The reputation of] Tarkovsky [has been] open to appropriation by the pseudo-religious illiberal ideology that has asserted itself in Putin’s Russia. The director has attained a canonical position in his homeland; there is a statue of him outside V.G.I.K. and a monument in Suzdal. As Sergey Toymentsev notes, latter-day Russian critics have linked Tarkovsky to Eastern Orthodox theology. Toymentsev counters that, although Tarkovsky was fascinated by religious iconography, he described himself as an agnostic. “The one thing that might save us is a new heresy that could topple all the ideological institutions of our wretched, barbaric world,” he once declared. Nor did he espouse conventional nationalist views. In his diaries, he wrote, “Pushkin is superior to the rest because he did not give Russia an absolute meaning.”

(The entire New Yorker piece can be read by clicking here.)

Without further comment, then, below I have posted the entire film twice — both the longer cut and the shorter cut (both have English subtitles) — and a few interpretive extras that are to be found on YouTube. The latter delve into the art of — and the various aspects of meaning to be derived from — this cinematic masterpiece.

One caveat: Andrei Riblev is a meditative experience — so skip the popcorn, pay attention, and reduce distractions. Marvel this isn’t.

The longer cut:

The shorter cut:

Extras:

Wow, this is an awesome suggestion. I think I'll watch it with my wife soon. I'm always looking for a good film that is actually thought provoking.

''Images are something beyond symbols, this is why I prefer them''-Tarkovsky

This was a quotation of his I heard a few years ago and his explination of symbols being something defined and images being something beyond that and him calling art preparing for death and stating he ''prayed through cinema'' I found facinating. I've watched some of Solaris and liked it quite a bit (I must be honest I still have to finish it). But I'll be sure to added theses to the grocies list in the back of my mind, thanks.