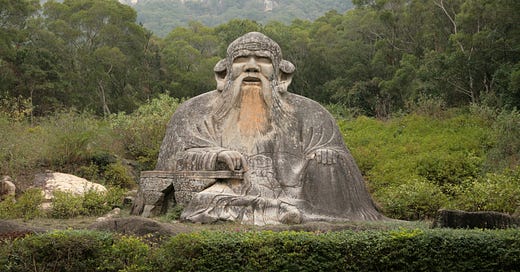

There is a being [wu] – formless, complete in itself [hun] –

Preceding Heaven and Earth

Tranquil, vast, standing alone, unchanging

It provides for all things yet cannot be exhausted

It is the mother of the universe

I do not know its name

so I call it “Tao”

Forced to name it further

I call it

“The greatness of all things”

“The end of all endings”

I call it

“That whi…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Pragmatic Mystic to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.