When I look over my meager literary output, I can truthfully say that I consider all of it – the fiction included – “religious.” Nor am I sure I would be capable of writing anything that was not, in some sense, religious. I have nine non-fiction books in print, one novel (a satirical “Gothic-thriller”), and most recently there has been added a collection of ghost stories, aptly titled Patapsco Spirits: Eleven Ghost Stories. My non-fiction is rightly categorized as “religion” or “spirituality,” although another book of mine published earlier this year – The Voyage of Life: The Sacred Vision of Thomas Cole – can also be pegged as “art history” and, in part, “biography.” But it’s my fiction books, arguably, that may constitute the truest writing I’ve done. They’re “true,” not in the slippery sense of facticity, not in the way “non-fiction” is considered “true”; they’re true in a more profound sense. I believe many fiction writers feel the same about what they write. Fiction comes from someplace within a writer that’s vaster and more mysterious than the mere intellect. Hence, works of fiction can often reasonably be said to be implicitly spiritual, conceived as they are in an act of contemplation. With that in mind, then, I want to discuss briefly my eleven published ghost stories and how they relate to the “pragmatic mysticism” I write about on this page.

With no hesitation, I can say that writing down those tales was indeed intimately linked to my “spiritual” practice. Many stories within the genre of the ghost story deal with perennial matters, and mine unquestionably do. I believe that we are all connected on the level of the psyche, that we participate in a collective unconscious; consequently, then, I also believe that the themes of my macabre tales – which perhaps seem obscure on the surface – can be sensed by perceptive readers in a way that bypasses the rational and logical mind. This is true of all fiction, of course, when it doesn’t fall into didacticism; but ghost stories have a peculiar way of getting under our mental “skin” right from the outset. Tales of spirits interacting with human beings are among the earliest yarns ever spun; they are found in every culture. And they are unpretentiously, unapologetically, and directly “spiritual” tales; they accept as their premise the commonly perceived reality of impermanence and death, while daring to point resolutely to a parallel reality existing beyond what the five senses can grasp.

When I talk about the ghost story, I’m not talking about “horror.” That distinction must be clear. A ghost story will almost certainly involve some element of horror simply because it inevitably deals with mortality, and mortality frightens us (even if we don’t admit it). But a ghost story doesn’t need the sort of “jump scares” that are – rather boringly now – expected in horror movies, or explicit exposure of the ghastly and ugly, for it to be unnerving. It doesn’t require gore or “body horror.” A ghost story might include such features as a given tale requires, but even when it does include the graphic, it shouldn’t betray the all-important element of subtlety. For me, if a ghost story ceases to be subtle and falls into the trap of cheap thrills, I lose interest in it.

By “subtlety” I refer to the sense of the mysterious, the inexplicable. Maintaining an atmosphere of mystery right up to the end is vital. “Reason” and logical explanations are not essential for a ghost story. It’s enough that something extraordinary is present and insistent and impinging on everyday existence. There doesn’t need to be any “back story” to satisfy the reader’s curiosity (a popular fad in fiction these days); there doesn’t even need to be a satisfying “wrapping up.” The reader can – and sometimes should – be left hanging, left with unanswered questions and a feeling of unease. In such tales, the protagonists find themselves in environments that have unexpectedly become unfamiliar to them, especially if the same environments seemed familiar and cozy before. The most important elements are, in fact, the environment and the atmosphere (an atmosphere that may shift from benign to malign in the course of the narrative). “Visually,” it can be any sort of environment – the more realistic and easily imagined it is by the mind’s eye, the better – but it must be an environment in which the unseen can be felt encroaching upon the protagonists (and the reader) more and more. The “weight” of the atmosphere must increase as the tale unravels. These are non-negotiables for a decent ghost story. Accept no substitutes.

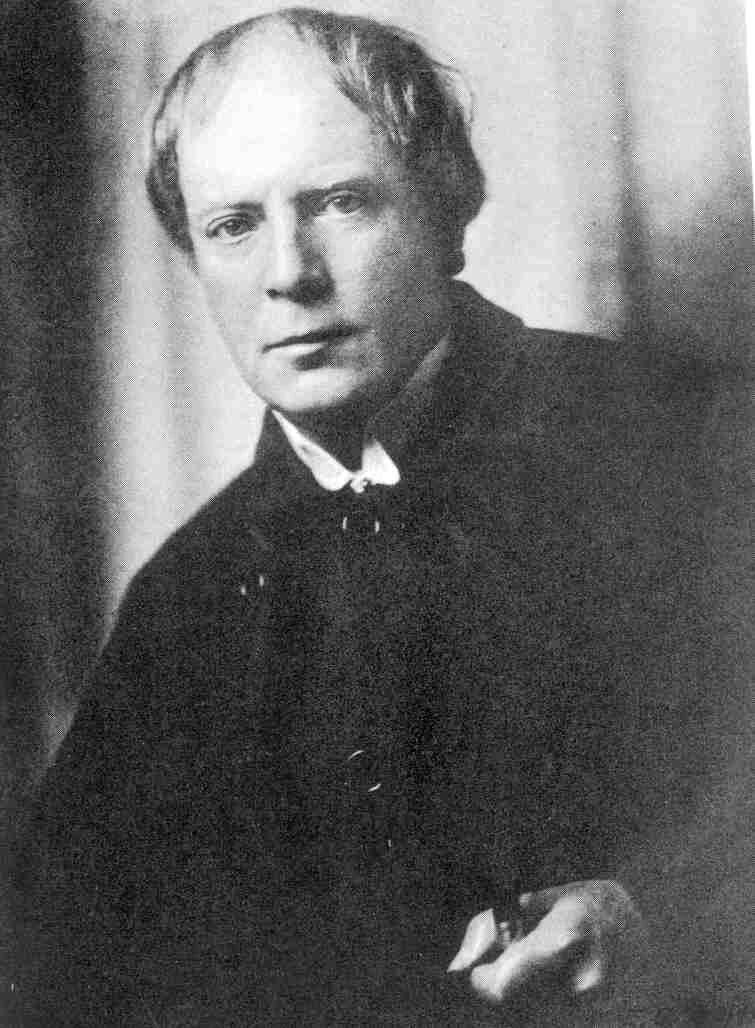

(Arthur Machen)

The eleven ghost stories I have written for my collection are, as I say, spiritual stories, and not just in the sense that they’re about spirits. The latter range from the demonic to the angelic, the unquiet dead to the protective souls of departed loved ones; there are shapeshifting tricksters, pukwudgies, and entities of dark and obscure origin inhabiting them. But these are spiritual stories, not because they depict such entities, but because they indicate an unseen order at work beyond the quotidian, a moral universe that envelopes and pervades the mundane. It may be a moral order that feels alien and uncomforting, like the whirlwind-riding deity of the book of Job, one that disrupts and unsettles and possesses uncanny power. When it intrudes, it shows itself in control, and no one, good or bad, can prevent its operations. The ghost story, then, is a reminder of forces that we can’t dominate – forces outside us and, more ominously still, forces that lurk within our psyches.

If this is a key element of the ghost story, it’s also one of genuine spirituality, regardless of the tradition one affirms (it’s also essential for healthy psychology). It’s too often overlooked or resisted, but one sign of mental and spiritual maturity is the realization that we’re not in control, that we’re fragile, that it doesn’t take much at all to knock us off our feet and on our backsides. It’s essential to spiritual and psychological growth that we come to accept as unavoidable in our lives the unexpected, the inopportune, the unwanted, and the frightening. Through the unpleasant experiences we all endure, we come to terms with inexorable forces that will alter us one way or another. Paradoxically, if we can develop an acceptance of our own comparative fragility in the face of these forces, the less fear and anxiety we will experience as time goes on, and the greater will become our ability to withstand with patience whatever else may come. This latter sense comes with age and maturity, one hopes, although it’s not guaranteed it will. We have to be attentive, learn, cooperate, and be willing to change (tip: meditation helps). One of the major themes in my ghost stories, then, is growth in spiritual maturity or – with dire consequences – resistance to it. The spirits in my tales stand as symbols of the forces we cannot dominate, restrain, cajole, or control. In the stories, these are preternatural entities, some threatening, some salvific. In real life, though, we are met with equally unruly forces every day and everywhere. Whether or not we discern a moral order revealed in their interference is largely up to us.

Finally, on a quite different matter related to the book, some have asked me whether or not I believe in literal ghosts. It’s one of those questions that’s frequently asked of writers of ghost stories. Arthur Machen and Charles Williams did believe in ghosts (both were devout Anglo-Catholics, as it happens). The patriarch of the classic ghost story, M. R. James (another churchman), was reticent in saying explicitly that he believed, but his last and shortest story – “A Vignette” – is said to be autobiographical. If so, it seems he did. Other writers in the genre have been avowed materialists, evincing nary a shred of belief. And so on.

(M. R. James)

But I do believe in ghosts and in a spiritual realm (and also a transcendent universal moral order that doesn’t always elicit comfort or pleasure, but which I must learn to trust). I have no idea what a “ghost” may be (I would hesitate even to say that a “ghost” is “immaterial” – what, really, do we understand, with our limited perceptions, about “matter”?). There seems to be a wide variety of phenomena that fall under the general, and evidently misleading, heading of “ghost.” Some are repetitive apparitions that don’t interact with those observing them, some are highly interactive and violently disturbing presences (what we call “poltergeists”), some are merely seen or heard or felt indirectly, some inhabit one locale, and some seem to become attached to individual persons and follow them wherever they go, and so on. Some seem to be the psychic projections of living persons; some seem to be lingering images or shadows of the dead; some seem to be “elementals” – animal-like (I’ve had some experience with that variety myself); some seem intelligent and unnervingly articulate... But, as I say, I have only the most fragmentary insights into ghostly phenomena. I will admit that I have had a few unremarkable experiences, but I know many others, whose veracity I would never have reason to question, who have had truly disturbing encounters. It’s easy for skeptics to write off such occurrences when they have never had an encounter with the extraordinary themselves (sometimes the proffered explanations of skeptics to those who actually have had experiences have struck me as more implausible than the accounts they try to explain), but I know former skeptics who did come face to face unexpectedly with the uncanny and, well, they aren’t skeptics any longer. The simple fact is that every culture since time immemorial has known and often chronicled ghostly phenomena. I would add, too, that the more one engages in spiritual practice and meditation, the fewer barriers there will be between the practitioner and the possibility of encountering spiritual phenomena. So, if you meditate, don’t be surprised if…

With these reflections, I present to you Patapsco Spirits: Eleven Ghost Stories. My wish is that you would find them to be not just tales about spirits, but also spiritually nourishing tales. And enjoyable ones.

Available everywhere. Here’s the Amazon USA page:

https://www.amazon.com/Patapsco-Spirits-Eleven-Ghost-Stories/dp/1621389294/ref=sr_1_9?crid=H1AKYIFLO1DQ&dib=eyJ2IjoiMSJ9._kbhjxrDZ0gMJ6_bmerE7tmZRMGBZ3vyN2xePbAveTMxVnPRyqWCBo57tjOe_QQn7IP9AzgELomHXki_yehD8ylcVXp9kka3cfTM2-ySAe3q3rhDkKPX3oJI8Kz8Q1Z-wxzZLOyXlSNx_mfDFIHbNHuQ2lTMaEPgg960d0bo7jYoySVR0D9g6DrZroP5VqhGQHUTVPgkgg21nUwivS5yzA.3qFk22dJ86rwS5AAXNK05ApzNTc4P2bQCBKqdsQdofA&dib_tag=se&keywords=addison+hodges+hart&qid=1751446733&sprefix=%2Caps%2C164&sr=8-9

I am new here and even newer to your writing more generally. Which is to say that what I've read of your work, your "meager literary output," as you modestly put it, exponentially pales in comparison. However these words of yours really hit home for me: "The spirits in my tales stand as symbols of the forces we cannot dominate, restrain, cajole, or control. In the stories, these are preternatural entities, some threatening, some salvific. In real life, though, we are met with equally unruly forces every day and everywhere. Whether or not we discern a moral order revealed in their interference is largely up to us."

You see, what a few too many more than I might care to admit have characterized as my already meager grip on sanity - my ability to discern moral order and consistently act with compassion thereby - was profoundly threatened by the interference of an utterly malevolent turn of spirit in my wife's psyche that haunted her unto death last year. Now, among other things, in writing here, I seek to support all efforts toward the possibility of ongoing discovery and engagement with salvific discernment in contemplative silence - which I am grateful to have been able to sustain and be sustained by throughout her 'illness' and death. From the little I've read of your much more than meager published work, I believe you are on about something similar, and I intend to continue drawing here on what is quite apparently the deep well of your discernment. Thank you!

Considering reading your ghost stories.

Your writing about them is compelling.

Thought l would share a poem by Mario Luzi, translated by l. L. Salomon:

Caught in the Light

Caught in the light, someone stirs between the walls . . .

perhaps it was you, now it's a ghost

or perhaps it's everything that has no peace,

place, motion and it's neither true

nor insubstantial-an empty thing that only

perfect mirrors reveal trembling.

An incorporated image, never at rest . . .

it is ours. I thought it a chimera

when someone uncensored appeared miraculously

under arid hillsides

on dark roads where nothing lives any longer,

nothing except hope for thunder.