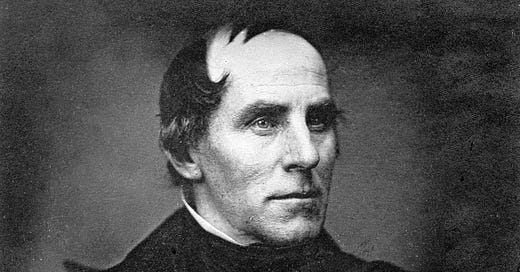

Next month, my book about the great English-American artist Thomas Cole (1801 - 1848) will be published by Angelico Press. The Voyage of Life: The Sacred Vision of Thomas Cole will mainly focus on his series of four large paintings, and the accompanying poem, that symbolically depicts the journey of human life from childhood to old age (“The Voyage of Life”). The book, as you might imagine, is more than an art history project, but a consideration of the wisdom one might discover in these powerfully evocative canvases. In the passage below, taken from the second chapter, I discuss the contemplative practice that informed Cole’s remarkable art.

*******

Cole’s biographer, Louis Legrand Noble, draws attention on more than one occasion to his subject’s love of solitude and contemplation. Noble was a clergyman in the Episcopal Church, as well as Cole’s close friend, a fellow poet, and a dabbler in “natural philosophy” (he was, it seems, impressively knowledgeable in Native American lore and language as well), so perhaps it should come as no surprise that he would highlight Cole’s spiritual nature in his biography. The Voyage of Life, like most of Cole’s works, reflects a temperament comfortable in its own company (“I am most happy when I can escape most from the world [of human traffic]”)[1], given to solitary reflection, and that looks upon the natural world with a keen eye, wonder, and awe. Noble informs us that Cole showed these tendencies from an early age. His family had come to America from Lancashire, England in 1819, when Thomas was eighteen. In that period of America’s history, the wilderness was both everywhere to be experienced and—as Thomas was to lament throughout his life—destroyed by the encroachments of civilization (the latter constitutes one of the most salient themes of his series of paintings, The Course of Empire). Cole sought to experience America’s natural wildness, then, at a time when it was undergoing domestication, exploitation, and ruin at the hands of industrialists and developers. In his sharp dislike for this state of affairs, he reminds us of Thoreau, and in fact there is some notable philosophical and spiritual commonality between Cole and Thoreau (and also Emerson).

Cole was not baptized into the church until 1842 when, at the age of 41, Noble himself baptized him. In his biography of Cole, though, Noble has no hesitation affirming that the former had always been a man of spiritual depth and a natural contemplative. By “contemplation” I mean precisely “religious” or “spiritual musing”—the word originally meant to be “with” or “within” an area or place (templum, temple) where augury or divination was practiced. To “contemplate” means to “look attentively” or “to behold” (in the case of divination, it meant to “look closely” or to “read” the signs), but the word has acquired over centuries of Western spirituality a quite different reference, that of solitary interior practice—silent meditation, in particular. This should not be confused with a state of mere passivity; on the contrary, it requires a mind that is alert and aware. It is a heightened mental state, one of wakefulness, not drowsiness or daydreaming. One detects almost a note of mysticism in Noble’s description of Cole’s attention to unspoiled nature—“a passion for nature was his ruling passion … The tones and expressions of the outer world found answering tones and expressions in his soul. He was beginning to behold in that something of himself, and to see in himself something of that.” That description is almost a meditation in itself.[2]

Cole wrote in his personal journal that “nature has secrets known only to the initiated. To him she speaks in the most eloquent language.”[3] If we were to ask, then, where Cole encountered the transcendent, beginning at an early age, the answer is clearly in the reciprocity between the nature he observed and the interiority he cultivated. The templum in which he contemplated was both within himself and within the natural world he encountered. He had an inner awareness of the mystical connection between himself and all things. Noble makes another remarkable observation about Cole’s interiority: “Cole clearly saw, and heartily rejoiced in the great and all-pervading principle of the universe, unity arising out of infinity. As in the humblest object, a pebble or a fungus, there is a hint, an expression of the infinite, so in the innumerable assemblage of all things there is a language eloquently expressive of unity. Infinitude in each; a harmonious union, a oneness out of all. To realize this was Cole’s, at an early period.”[4]

There was a stage in the development of Cole’s art that Noble describes as a sudden revelation that came to him. He had been dissatisfied with his early efforts. They struck him as mere imitation, stiff and lifeless, lacking vitality and feeling. Then, all at once, it dawned on him how he might rectify that deficiency and transform his art into animated (in the sense of possessing “soul”), vibrant renderings of his subject matter. It would require a meticulous, focused, methodical attention to what he observed—a sort of open-eyed, almost Zenlike gaze, scrutinizing every detail in an ascending order. “Hitherto,” Noble explains, “he had been trying mainly to make up nature from his own mind, instead of making up his mind from nature. This now flashed upon him as a radical mistake.” The result of this sudden realization on Cole’s part was that he adopted an entirely new practice:

At its first and last light, many a spring, summer, and autumnal day found him on the wild banks of the Monongahela [River], carefully drawing, from the crinkled root that lost itself in the mould to “the one red leaf … on the topmost twig that looks up at the sky”—to the mountain-line on the skirts of the sky—to the clouds far up in the sky, and the blue sky far away from the clouds.[5]

Note the “ladder of ascent” here, how Cole’s eye is said to have roved up and up, step by step, from the minutiae of the vegetal to the infinity beyond the horizon. This rigorous practice of an ascending observation from the roots of trees to the vastness of the sky, taking in everything in between, becomes evident to us when we examine a painting of Cole’s in the knowledge that this was his procedure. Cole directs our gaze ever beyond and deeper. He became a master of depicting “depth,” so important to landscape painters in the West from the Renaissance onward.

Some pages further on, Noble gives us yet another stirring glimpse of Cole’s practice of looking in wonder at scenery, even at landscapes he had seen many times before, in search of what Noble calls, without defining it, “spirit”:

He went, at the hundredth time, as one going for the first time—not in words, not in outward excitement, but in all gentleness and quietness, and in spirit, for he went to seek spirit: and when he found it under the shuck and crust of things, shuck and crust were all beating and throbbing with life; they were living creatures, ever beautiful, ever new: and so the last time of looking was as the first, and nature grew to him youthful instead of older, and covered tokens of heaven and immortality in its mouldering trunks, as ashes cover the living coals.[6]

This is a lovely passage, evocative in its depiction of what Cole saw in nature; it is likewise a very accurate description of what he put on canvas.

When we look at one of Cole’s renderings of natural grandeur, we are struck by two things: first, its attention to the actual details of what he saw, and second, that it is simultaneously a transfigured landscape. Something of the numinous shines through it—his style isn’t simply realistic. Cole, like other Romantic painters, gives us nature as a sacrament, an “outward and visible sign of an inward and spiritual grace.” Cole would have agreed with the sentiment accredited to Meister Eckhart, that every natural thing is a word of God—everything, that is, has something innate to it, that lies also beyond it, which that thing manifests. “The world is charged with the grandeur of God. / It will flame out, like shining from shook foil.”[7] Evelyn Underhill wrote:

In those hours [when the sense of beauty is felt], the world has seemed charged with a new vitality; with a splendour which does not belong to it but is poured through it, as light through a coloured window, grace through a sacrament, from that Perfect Beauty which “shines in company with the celestial forms” beyond the pale of appearance.[8]

As florid as Underhill’s description might seem to us today (she wrote it in 1911), it nevertheless accords with a Romantic sensibility that Cole shared. What he was after was the truth that lay behind what he was portraying. If all things “live, move, and have their being” in God [9], as Cole believed, then we could say that Cole endeavored to make his portrayals of the sublime and beautiful reflective of that belief.

[1] Noble, Life and Works, 151.

[2] Ibid., 11. Emphasis added. This sentence of Noble’s puts me in mind of that passage in Martin Buber’s I and Thou, in which Buber speaks of contemplating a tree: “I contemplate a tree… But it can also happen, if will and grace are joined, that as I contemplate the tree I am drawn into a relation, and the tree ceases to be an It…” Martin Buber, I and Thou, trans. and annot. by Walter Kaufman (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1996), 57–58.

[3] Noble, Life and Works, 41.

[4] Ibid., 56. Emphasis in the original.

[5] Ibid., 23–24. See also: McGilchrist, The Master and His Emissary, 247: “Even to attend to anything so closely that one can capture its essence is not to copy slavishly. To Ruskin it was one of the hardest, as well as one of the greatest human achievements, truly to see, so as to copy and capture the life of, a single leaf – something the greatest artists had managed only once or twice in a life time: ‘If you can paint one leaf, you can paint the world.’ Imitating nature may be like imitating another person’s style; one enters into the life. Equally that life enters into the imitator.”

[6] Noble, Life and Works, 54.

[7] Gerard Manley Hopkins, “God’s Grandeur.”

[8] Evelyn Underhill, Mysticism: A Study in the Nature and Development of Man’s Spiritual Consciousness (New York: Meridian Books, 1956), 22.

[9] Acts 17:28.

(All the pictures above are taken from Wikimedia Commons, and are public domain.)

Everything here is meaningful and true to life. In this descriptive writing and in these paintings there is a “depth” depicted that is all important, a true lifelike depth that seems to be always what is missing in any photograph.

I find Cole's painting "The Oxbow" a perfect depiction of an American Arcadia.