There is a kind of meditation for which I feel not merely distaste but something akin to horror. Without giving details of my own experience – and I’ve done my fair share of experimentation in these things – I’m confident enough to maintain that there are forms of meditation one would be wise to avoid. Not being as wise as I should have been in years gone by and having gotten myself much too close to “the edge” in the process, I believe I can offer some cautionary advice to those similarly drawn to a quest for “contemplative experience.” And my very first piece of advice is not to seek “experience” at all, which is also what most “experienced” contemplatives would likewise advise. If one is a Christian, then I can say — with the backing of the vast majority of the greatest Christian spiritual masters — seeking and even having “experiences” are more likely than not to be distractions from the real purpose not only of contemplation but of life in Christ itself (as we will touch on below). But I am getting ahead of myself. Before going on, allow me to give a single example of the sort of meditative path – both the theory and practice – that I have in mind and would caution others not to tread.

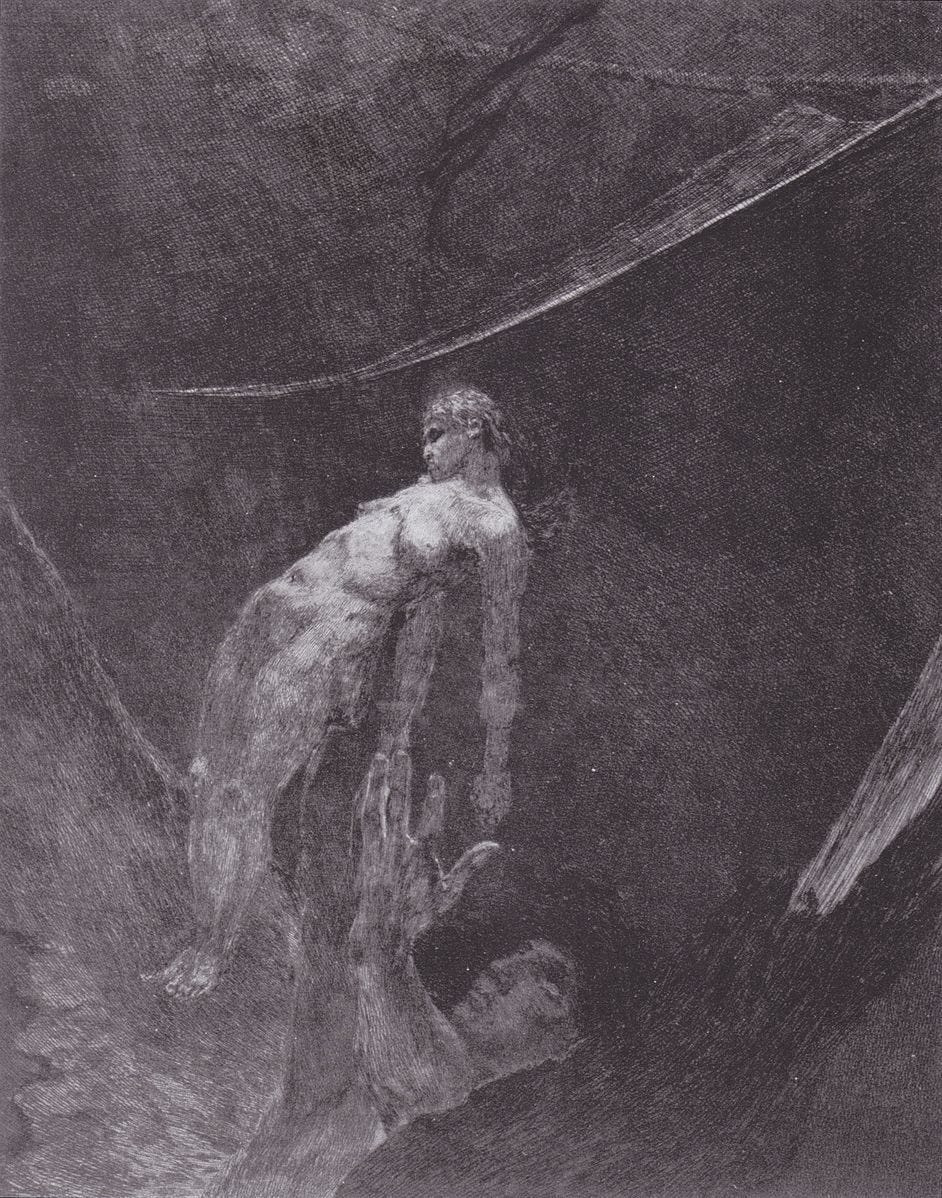

(Max Klinger, Back into Nothingness (Opus VIII, Plate 15/15), 1884)

My example concerns a Zen teacher of past acquaintance. He was a Westerner, a convert from Christianity (his church experience had been a nasty one), trained austerely in an Asian country I will not name, was ordained, and eventually became a respected Zen master back in the West. I liked him – as I have liked others with similar stories – but I was also disturbed by specific traits he exhibited. One recurring feature that showed up in his Zen teaching was the public denigration of “religion” – Christianity in particular and the “Abrahamic faiths” in general. As I mentioned parenthetically, he had an unfortunate personal history, so one might understand the damage inside him; unfortunately, the disdain he expressed in public (sometimes coarsely) was, in fact, a hatred that frequently verged on the generally misanthropic. (His abhorrence of “religion,” incidentally, was somewhat comical; here was a man dressed in the robes of a monk, striking gongs, burning incense, chanting sutras, leading others in arcane ritual practices, and so on, who quite unironically claimed to detest all the trappings of religion. The mind boggles.) Concomitantly, he became an enthusiastic fan (I can’t think of a more appropriate word) of the “New Atheists” when they first appeared and endorsed the popular materialist scientism they were facilely espousing. As his worldview developed under these influences, there could be no possibility of real or participatory transcendence; at the same time, as he believed, everything we think we know and perceive is illusory, and the purpose of meditation is to realize this at the deepest point of our being – to encounter the void, the empty “now.” Somehow, in this philosophy, such a realization constitutes precisely the liberation everyone most needs, the purest expansion of human consciousness. And given the supposed necessity that all should achieve this realization, the imperative for him was to go into all the world and proclaim the good news.

Now, perhaps I exaggerate (although I doubt it) and perhaps he would have explained the matter more eloquently than I have (after all, he was trained in it), but I could only conclude, after poring over his presentations, that this was indeed the gist of it. I could have argued with him (I’m sure I made some feeble attempts), as I have in past posts here [1], that Zen – deriving as it does from a Taoist view of reality even more than it does from a Buddhist one – classically does have a transcendent aim, that its language doesn’t preclude what we might call “God,” that it is unapologetically a religious way of seeing the cosmos, that “emptiness” in its schema refers to a burgeoning and self-giving reality, and that scientism is not conceptually congruent with it — but I know it would have met with an impermeable materialistic wall of determined resistance. The most alarming aspect of his teaching about meditation in my opinion, however, was that meditation should be a striving after an experience of nothingness and emptiness. His determination to promulgate this meditative nihilism (there’s no better term for it) to others was indefatigable.

Now, it must be said that Christians are not unfamiliar with similar concepts of “nothing” and “emptiness,” but for us, these are states of the psyche that we must pass through as we press on in our encounter with God. They are not where we are meant to end up. We intend to get past them, and at the same time, we know that we may well need to go through them again and again. What my friend denied was, simply put, that there was anything – and certainly any living, relational being – beyond the experiencing of the primordial emptiness in all things.

The reason I find this sort of meditation distasteful and worse is that its only outcome (unless that is, one finds in the darkness an unexpected light piercing through from the other side) is to get stuck there or to end in despair. One can get stuck in the feeling of oblivion because, for some practitioners, there’s a kind of pleasurable aspect to it. Like the effects of a narcotic, it can cancel out one’s surroundings – with all the attendant noise and clamor and annoying people (again, there was not a little misanthropy in my friend’s outlook) – and one can find there an interior womblike sense of safety. Nothingness, of course, can never really be achieved (the closest I’ve ever come to that were the three times in my life when I was anesthetized for surgery), but some forms of meditation can get one near enough to it for the feeling to be addictive. There can be (though not always!) a feeling of bliss accompanying it. The other outcome is the despair that can develop in a practitioner when it dawns on him or her that this is all there is to it. Both the theory and practice end in – what, exactly? “Nothing,” which really isn’t, isn’t very much in the long run to go on. Of course, some assert cheerily that this realization of sheer emptiness transforms our consciousness so that we can now relax, cease worrying, and look at everything and everyone as together inhabiting a grand, insubstantial illusion – we can now sit back and enjoy “life’s show.” But, speaking for myself, if I were to believe that this is all there really and truly is, I know where I would end up: in despair. I would not be capable of wallowing in such self-indulgent banality without eventually succumbing to a deep disgust with living – and I’m quite certain I’m not alone in thinking this way.

The Christian concept of contemplative prayer is very nearly the antithesis of what I have tried to describe above. For one thing, it isn’t a quest for either “experience” or “emptiness.” It is essentially an ongoing interaction with God, “in whom we live and move and have our being” (see Acts 17:28). There can be no misanthropy in it, no hatred (even of one’s enemies), no seeking for the bliss of oblivion, and no despair (which Christianity has always viewed as worse than sin). Through liturgy, word, and sacrament, our bodies and souls are brought into the fellowship of the Spirit. Jesus Christ – God in human flesh – has joined his life and death to ours and, in rising from the dead, has given us the assurance of our sharing in the divine nature itself (see 2 Peter 1:4). When we contemplate or meditate, we do not meditate on nothingness, but on “the image of God in Christ”: “Now the Lord is the Spirit… [A]ll of us with face unveiled, mirroring the Lord’s glory, are being transformed [or, transfigured] into the same image, from glory to glory, as by the Lord, the Spirit” (2 Cor. 3:18). Nothingness and darkness are receding in us, even when they seem at times to be overwhelming us (“[T]he light shines in the darkness, and the darkness did not overcome it”; John 1:5), because what has appeared and is growing in brightness within our souls – the darkness notwithstanding – is the primordial light of creation itself: “[T]he God who says, ‘Light shall shine out of darkness’ is the one who has shown in our hearts, for illumination of the knowledge of God’s glory in the face of Christ” (2 Cor. 4:6; see Genesis 1:3).

Thomas Merton, in his small classic Contemplative Prayer, addressed vividly the “spiritual” draw to meditative nihilism, in a chapter dealing with “quietism” (not so much with the seventeenth-century movement in mind, but more generally), and I will conclude here with his wise words:

[W]e must not take a purely quietistic view of contemplative prayer. It is not mere negation. Nor can a person become a contemplative merely by “blacking out” sensible realities and remaining alone with himself in darkness… He becomes immersed and lost in himself, in a state of inert, primitive and infantile narcissism. His life is “nothing,” not in the dynamic, mysterious sense in which the “nothing,” nada, of the mystic is paradoxically also the all, todo, of God. It is purely the nothingness of a finite being left to himself and absorbed in his own triviality…

[T]here is a temptation to a kind of pseudo-quietism… And this leads… to a deliberately negative spiritual life which is nothing but a cessation of prayer, for no other reason than that one imagines that by ceasing to be active one automatically enters into contemplation. Actually, this leads one into a mere void without any interior, spiritual life, in which distractions and emotional drives gradually assert themselves at the expense of all mature, balanced activity of the mind and heart. To persist in this blank state could be very harmful spiritually, morally and mentally…

True contemplation is not a psychological trick but a theological grace. It can come to us only as a gift, and not as a result of our own clever use of spiritual techniques…

Emptiness might just as well bring us face to face with the devil [as with God], and as a matter of fact it sometimes does. This is part of the peril of the spiritual wilderness. The only guarantee against meeting the devil in the dark (if there can be said to be a guarantee at all) is simply our hope in God: our trust in his voice, our confidence in his mercy.

Hence the contemplative way is in no sense a deliberate “technique” of self-emptying in order to produce an esoteric experience. It is the paradoxical response to an almost incomprehensible call from God, drawing us into solitude, plunging us into darkness and silence, not to withdraw and protect us from peril, but to bring us safely through untold dangers by a miracle of love and power.

The contemplative way is, in fact, not a way. Christ alone is the way, and he is invisible. The “desert” of contemplation is simply a metaphor to explain the state of emptiness which we experience when we have left all ways, forgotten ourselves and taken the invisible Christ as our way. [2]

[1] See this post in particular.

[2] Thomas Merton, Contemplative Prayer (New York, 1969), pp. 90 – 92.

I have always been under the impression that the concept of "emptiness" in Zen Buddhism is not at all a reference to some sort of nihilistic image of nothingness, but rather references a state of mind where the practitioner overcomes their mind's habit of "objectifying" or "categorizing" the world into individual parts, and rather experiences the world "all at once" as a singular, unitary being which their mind is a part of.

The word "emptiness" is not a moniker for "nothingness", but a reference to a realization of existence as "empty" of the form which our minds impose upon it.

Addison, another bullseye hit! As a practicing Christian who has some interest (though less of late) in what Zen has to teach us, the one area of Zen I've struggled with is the implication of nihilism - the worst of all philosophies, especially if true. I realize Zen doesn't teach nihilism but I wonder about the implications of non-theism and non-self and how that cashes out in everyday life. To me, and I know I’m biased, the implications of non-theism and non-self point towards nothingness which I cash out in terms of despair, not hope. A grossly simplistic observation: my internal landscape seems to prefer a personal God which ‘guarantees’ victory and divine order and vindication in the end (think of the end of the book of Revelation) over the Buddhist concept of nirvana where the self is swallowed up into the whole (think of the self as a drop of water that is poured into the ocean). Existentially, Buddhism can lean towards ‘feeling’ nihilistic and without purpose to me, though I know intellectually this is not the case (or need not be), which your article nicely reflects - thank you.