At first blush, the words “pragmatic” and “mystic” would appear to be incongruent. If someone is “pragmatic” – by which we usually mean “sensible,” “level-headed,” “down-to-earth,” and so on – we wouldn’t expect him or her to be a “mystic” as well – by which we frequently mean “dreamy,” a student of the arcane, a sort of magician who speaks in riddles and wears odd clothes and headgear, and so on. I recall a sermon from many years back, in which the priest referred to himself as “doctrinally pragmatic” and then, attempting wit, went on to warn us all against the dangers of mysticism by describing it as beginning in a “mist” and ending in “schism.” I was in my early twenties at the time, serious and not easily amused, and had already read the entire oeuvre of John of the Cross, the two then-available collections of writings from The Philokalia, Evelyn Underhill’s magisterial study, Mysticism (published in 1911), not to mention Indian and Chinese classics such as the Bhagavad Gita and the Tao Te Ching, etc., and right there and then I lost all interest in whatever else the man in the pulpit had to say. It was a lesson to me never to speak in public about “big” subjects that require doing at least minimal homework beforehand. But, back to the point, pragmatism and mysticism – in the minds of some at any rate – would seem to go together just as naturally as a lobster and a telephone do. Yet here I am, putting lobsters and telephones together and calling this page “The Pragmatic Mystic,” and doing it, not just to be contrary or provocative, but because I believe that healthy mysticism should be clear-sightedly pragmatic in nature.

In this post and the next (in between which I plan to offer a “special” Christmas post next week), I want to define terms that categorize four features that have come to characterize my own approach to the inner life. In addition to “Mysticism” and “Pragmatism,” the other two terms, which also could be seen as somewhat incongruent, are “Perennialism” and “Individuation” – but more about the latter two next time. In what follows, I would like to focus on the first pair, not exhaustively defining them but instead highlighting only what I see in them as useful to us (and referring here to their “usefulness” should already clue you in to my relentlessly pragmatic bent).

So, one at a time.

I think the most significant word – the one with an accumulation of barnacles attached to it that need some scraping off – is Mysticism. I very nearly hesitated to use it here, except that all the other options seemed to be weak tea by comparison. “Piety” is too precious for modern sensibilities. “Contemplation”/”contemplative” – wonderful words that we’ll certainly use again and again – sound too elevated in tone to my ears to use in a title, and “contemplation” doesn’t contain as much meaning as I wanted to see packed into a single word. “Spirituality” is simply dull; it’s been overused and, consequently, has come to mean virtually nothing as a result. I will sometimes use the word in a pinch, but that’s all. But “mysticism” is, despite the naysayers, a robust word. It has meat on its bones. It offers something nutritious for rumination.

The word comes from the Greek μύω (myo) meaning “to conceal,” and its derivative μυστικός (mystikos) refers to someone who is “initiated” into “mysteries” or “hidden things/truths.” I have no intention here of tracing the history of the word, which can be found online and off, but rather to focus on its characteristics, and one obvious characteristic is that it applies – unlike, say, “spirituality” – to those persons who are seriously engaged in the pursuit of what is “hidden” from view but is felt or known instinctively to be real.

As the word has come to be used by those with some understanding of its implications, it means primarily a disciplined reliance on intuition and introspection for the sake of apprehending what underlies, permeates, and transcends everything our common senses and reason are able to grasp. (I ask you to re-read that last sentence once or twice carefully – every word of it is precise.) It is a search for presence – whether that presence is understood as “personal” or “non-personal” – but a presence that can only be perceived in stillness, openness, and by reducing the restless flow of thoughts, or what Buddhists call “the monkey mind.” (Somewhat related to this idea of basic and transcendent “presence” being perceived as personal and/or non-personal, I’m reminded of the story about Sri Ramakrishna, who, when asked by a Western theologian to comment on God, replied: “Do you wish me to talk about God with qualities (sa-guna) or without qualities (nir-guna)?” Ramakrishna’s question-answer was meant to bring that theologian “to the brink of the abyss that lies beyond all human knowing.”[1]) Most of us have experienced awe and wonder in an unprecedented personal encounter with nature, for example. Many of us would concede that we intuited a “presence” in such moments, whether it felt “personal” or not. We can, of course, discount such flashes and intimations as “woo-woo” and “just our feelings,” subjective only, with no corresponding object; but I think that, if we do, we’re tossing aside important invitations to interact with reality with those latent capacities we all have. “Invitations” from what or whom, we might well ask. But right there, in those moments, is the seed of mysticism; if we cultivate it, it will grow.

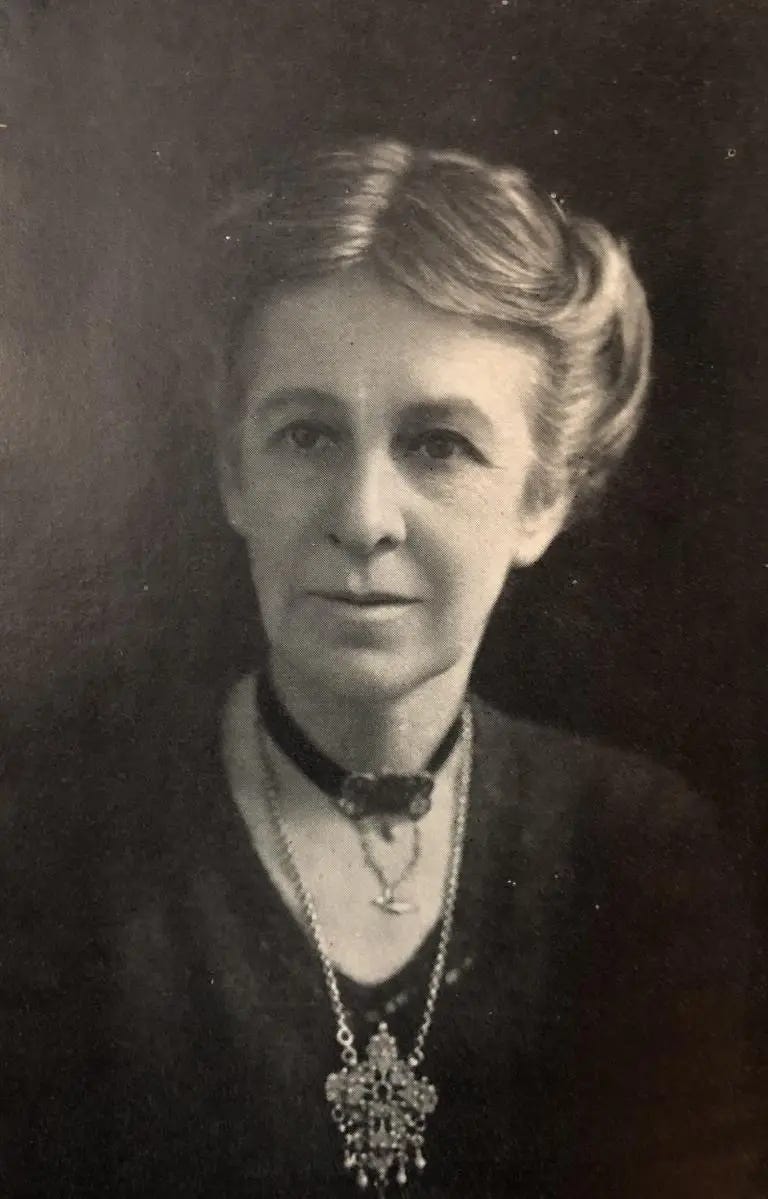

In her great book on the subject, Evelyn Underhill (1875 – 1941) makes this incisive statement, and it’s well worth chewing on and thoroughly digesting:

Of all those forms of life and thought with which humanity has fed its craving for truth, mysticism alone postulates, and in the persons of its great initiates proves, not only the existence of the Absolute, but also this link: this possibility first of knowing, finally of attaining it. It denies that possible knowledge is to be limited (a) to sense impressions, (b) to any process of intellection, (c) to the unfolding of the content of normal consciousness. Such diagrams of experience, it says, are hopelessly incomplete. The mystics find the basis of their method not in logic but in life: in the existence of a discoverable “real,” a spark of true being, within the seeking subject, which can, in that ineffable experience which they call the “act of union,” fuse itself with and thus apprehend the reality of the sought Object. In theological language, their theory of knowledge is that the spirit of man, itself essentially divine, is capable of immediate communion with God, the One Reality.[2]

There’s a lot to unpack in that, not least what is meant by “God” (a subject I’ll come back to in a future post at some length), but I’ll leave the topic of mysticism there for the time being and turn my attention now to Pragmatism and what I’m referring to in these posts when I use that term.

To do that, I will resort to quoting myself. In my book Strangers and Pilgrims Once More: Being Disciples of Jesus in a Post-Christendom World I discussed Pragmatism at some length. There I wrote:

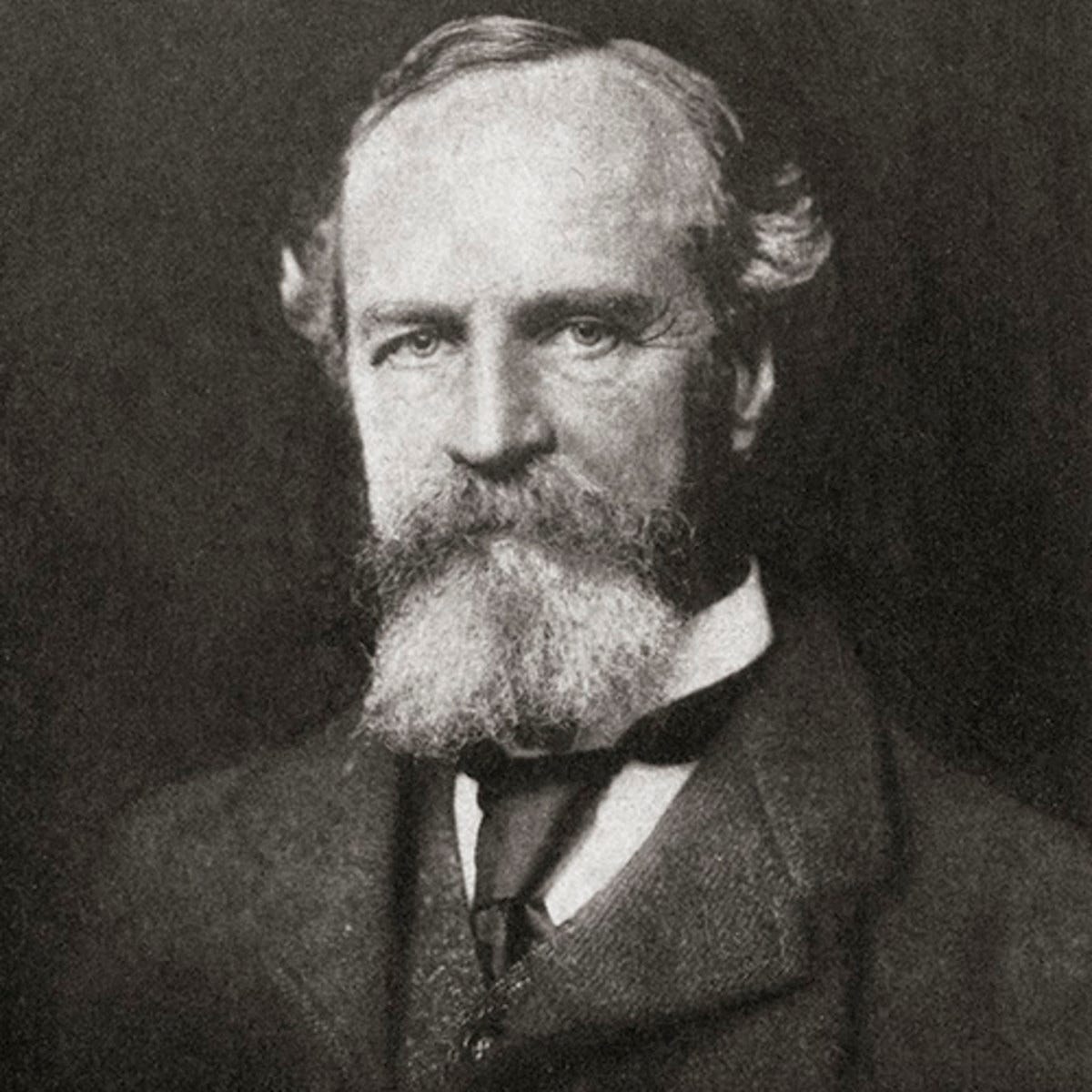

Historically, Pragmatism is a distinctively Anglo-American philosophical school, having to do with ideas that “work” in contrast to those that don’t, or at least are so disconnected from real life that they don’t much matter. As schools of philosophy go, it’s an eminently sensible one. Pragmatism is associated with such distinguished names in the history of American thought as Charles Sanders Peirce (1839 – 1914; his surname is pronounced “purse”; and he is alleged to have been Pragmatism’s originator through an article published in 1878), Josiah Royce (1855 – 1916), John Dewey (1859 – 1952), and – most eccentrically – George Santayana (1863 – 1952)… Arguably, it was William James (1842 – 1910) who made it generally winsome and persuasive as a philosophy, especially in the 1906 – 1907 series of lectures he presented both at the Lowell Institute in Boston and at Columbia University in Manhattan, and later published as the small book Pragmatism.

As James explained, the word “pragmatism” comes from the Greek for “action” (pragma), and is related to other English words such as “practice” and “practical.” As already noted, Pragmatism is in fact concerned with practicalities: What, say, are the practical results of believing this as opposed to believing that? What are the real consequences if I hold such-and-such to be true or to possess meaning?

Its boldest claim, perhaps, has to do with the nature of truth… [I]n the words of William James, “The true is the name of whatever proves itself to be good in the way of belief, and good, too, for definite, assignable reasons.”[3]

In Pragmatism, James makes it clear that he is talking about a method, not a doctrine or a system of philosophy. It is a method of discovering what’s true or what “works” for oneself – James, American through and through, speaks of it as a way of discovering the “practical cash-value” of any given idea (and being an American myself, I take some stock in the analogy of “cash-value”). He writes:

Pragmatism unstiffens all our theories, limbers them up and sets each one to work. Being nothing essentially new, it harmonizes with many ancient philosophic tendencies…

Against rationalism as a pretension and a method pragmatism is fully armed and militant… It has no dogmas, and no doctrines save its method…

No particular results then, so far, but only an attitude of orientation, is what the pragmatic method means. The attitude of looking away from first things, principles, ‘categories,’ supposed necessities; and of looking towards last things, fruits, consequences, facts.[4]

To put it very succinctly, then, pragmatism is empirical in nature: you have to experiment, to act, in order to know. It seeks, as James would have it, fruits and not just roots. Theory alone is insufficient in the quest for what matters; doctrines and dogmas may be pointers to truth, but it’s the actual encounter or experience of truth that matters above all else. “For what seriousness can possibly remain in debating philosophical propositions,” asks James in his monumental The Varieties of Religious Experience, “that will never make an appreciable difference to us in action? And what would it matter, if all propositions were practically indifferent, which of them we should agree to call true or which false?”[5] And Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel (1907 – 1972), remarking on the subject of dogma, wrote in a similar vein: “Teachers of religion have always attempted to raise their insights to the level of utterance, dogma, creed. Yet such utterances must be taken as indications, as attempts to convey what cannot be adequately expressed, if they are not to stand in the way of authentic faith.”[6] (That authoritative “statements of faith” can “stand in the way of authentic faith” is something we must take quite seriously. But we’ll save that for another time.)

So, then, we come back around to mysticism. As perhaps we can see, it doesn’t clash with pragmatism at all – in fact, the very nature of mysticism is and must be pragmatic. And it’s for this reason that mystics have been, again and again, thorns in the side of the guardians of institutionalized religion over the centuries. Because mysticism is an interior practice, it’s something that can only be done by each person alone, even when it’s supported by a fellowship of others. It’s empirical and experimental, ever seeking results, and it can’t easily be policed by spiritual authorities (one only need scant acquaintance with, say, the story of Marguerite Porete in the 13th and 14th centuries, or the imprisonment of John of the Cross in the 16th, or the sad affair of the Quietist movement in the 17th, to see extreme examples of how mysticism has sometimes faced suppression and violence). When it is healthy – staying clear, that is, of the various temptations of dreaminess, superstition, wishful thinking, sentimentalism, rationalism, and so on – then its “practical cash-value” will in time prove itself. The practitioner will be changed by it over time (and it will take time, indeed a lifetime if done right), she or he will deepen inwardly and will see the world and others in the light of something more, though not without life’s attendant difficulties and inner wrestling.

But more about those things in future posts. This is a good place to pause. Next time: Perennialism and Individuation.

***

This post and the next will be available to everyone – actually, the next two will be available to all, since I intend to publish a “bonus” Christmas post next week of an entirely different nature. I hope you like ghost stories.

After that, I will aim the majority of posts at paid subscribers. But I will (hopefully, each month) publish something worthwhile for everybody and not just for paid subscribers. I hope you hang in and invite others.

[1] Stephen and Robin Larsen, Joseph Campbell: A Fire in the Mind (Rochester, VT, 1991), p. 283.

[2] Mysticism: A Study in the Nature and Development of Man’s Spiritual Consciousness (New York, 1956), pp. 23 – 24.

[3] William James, Pragmatism, Library of America edition (New York, 1987), p. 520; A. H. Hart, Strangers and Pilgrims Once More (Grand Rapids, 2014), pp. 43 – 44.

[4] James, ibid., p. 510.

[5] James, The Varieties of Religious Experience, Library of America edition (New York, 1987), p. 399.

[6] Heschel, God in Search of Man: A Philosophy of Judaism (New York, 1955), p. 103; italics mine.

Good stuff, thanks. Early days, of course, but I think this might prove to be right up my alley; it's worth a subscription to find out.

Thank you, sir. Very stimulating.